Hubbell and Benes: Designers of West Side Market, Wade Chapel, Art Museum, Masonic Auditorium

The early 1900s mark an era notable for the work of some of Cleveland’s finest architects, and the buildings designed between 1903 and 1916 by Benjamin Hubbell and W. Dominick Benes remain among the most loved.

They include some of the city’s most recognizable public spaces.

The firm’s senior partner, W. Dominick Benes was born in Prague in 1857. His parents left Bohemia to emigrate to Ohio nine years later. Leaving high school at age 15, Benes began a three-year apprenticeship under Cleveland architect Andrew Mitermiler.

Benjamin Hubbell’s background was substantially different. He was born in Kansas in 1867 and held a Master of Science in architecture from Cornell University.

The partnership between Hubbell and Benes began in 1897 and their firm remained in operation until 1939.

Their first commission remains one of their most noteworthy—Wade Memorial Chapel located in Lake View Cemetery. This structure was conceived in 1896 by Jeptha H.Wade II, a patron of the arts who helped found the Cleveland Museum of Art. He intended the chapel as a memorial to his grandfather, Jeptha Wade I, a founder of the Western Union Telegraph Company.

Wade Memorial Chapel – Lake View Cemetery

Wade Memorial Chapel – Lake View Cemetery

Wade was so pleased with the proposal offered by Hubbell and Benes that he chose not to consult any other architects. The structure was built of granite quarried in Vermont. The quantity necessary was so large that 40 rail cars were needed to transport it to Cleveland. The building was completed in 1901.

The actual cost of the chapel is a disputed number, but it is agreed that the equivalent cost today would amount to several million dollars. The Tiffany stained glass windows decorating the interior were also costly. Wade placed no limit on the construction budget.

The Citizens Building built in 1903.Another interesting Hubbell and Benes structure is the 14-story Renaissance Revival Citizens Building, 840 Euclid Ave. An early commission for the firm by Citizens Savings and Trust, plans were drawn in the summer of 1900 on a lot that housed a two-story building that was once a high school and subsequently used by the Cleveland Public Schools and the Cleveland Public Library. Citizens bought the land and the building at auction and proceeded to hire Hubbell and Benes for the design of a new building.

The Citizens Building built in 1903.Another interesting Hubbell and Benes structure is the 14-story Renaissance Revival Citizens Building, 840 Euclid Ave. An early commission for the firm by Citizens Savings and Trust, plans were drawn in the summer of 1900 on a lot that housed a two-story building that was once a high school and subsequently used by the Cleveland Public Schools and the Cleveland Public Library. Citizens bought the land and the building at auction and proceeded to hire Hubbell and Benes for the design of a new building.

Construction was delayed by a dispute with architect Levi Scofield, whose own Scofield Building was under construction to the immediate east of the proposed Citizens Building.

The structures were to share a common wall, and disputes over the thickness and design of this wall nearly led to a lawsuit. The matter was settled out of court and construction proceeded. The Citizens Building was completed in 1903.

A distinctive feature of this building was the Neoclassical portico marking its entry. Four 30-foot granite columns supported a triangular decorative panel referred to as a tympanum. This was carved from a single piece of granite by Little Italy icon and stonemason Joseph Carabelli, and contained allegorical figures representing banking and commerce.

This exceptional aspect of the building was destined to be short lived. Purchased by the Guardian Trust Bank in 1924, the new owner’s first move was to order the destruction of the portico to create retail space—extending the building’s ground floor by 17 feet to reach the Euclid Avenue sidewalk.

But the new owners weren’t destined to enjoy the building for very long. Less than 10 years later, on February 25, 1933, a run on the bank led to the loss of half of Guardian Trust’s deposits in a single day—sending the bank into receivership.

The former Citizens Building has remained a desirable business address and for nearly 25 years been known today as the City Club Building.

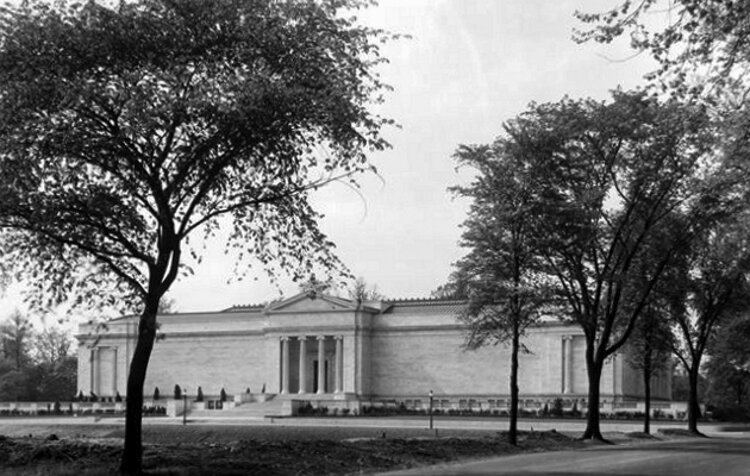

Cleveland Museum of Art in 1916The Cleveland Museum of Art’s original 1916 structure remains the focal point of the museum more than a century later. An excellent account of the museum’s early days can be found in William Milliken’s book, “A Time Remembered.” The construction of this building is a remarkable example of cooperation as several independent bequests were coordinated by heirs to build one extraordinary art museum instead of several lesser ones. The structure is arguably the firm’s finest building and remains one of Cleveland’s most significant cultural sites.

Cleveland Museum of Art in 1916The Cleveland Museum of Art’s original 1916 structure remains the focal point of the museum more than a century later. An excellent account of the museum’s early days can be found in William Milliken’s book, “A Time Remembered.” The construction of this building is a remarkable example of cooperation as several independent bequests were coordinated by heirs to build one extraordinary art museum instead of several lesser ones. The structure is arguably the firm’s finest building and remains one of Cleveland’s most significant cultural sites.

Other Hubbell and Benes gems include the 1912 West Side Market which continues to serve Cleveland residents 110 years later.

The 1921 Masonic Auditorium on Euclid Avenue is a massive structure which has been the headquarters for the Freemasonry’s Scottish Rite Valley of Cleveland for the past century. In its earliest days it hosted many concerts presented by the Cleveland Orchestra before the construction of Severance Hall in University Circle.

Another interesting survivor is Hubbell’s 1929 estate, Playmore, located in Kirtland. Newly restored, this 13,000-square-foot mansion was recently offered for sale at a price of nearly $1.5 million.

With the exception of the privately-owned Playmore, these buildings remain accessible to the public and in daily use, entering their second century of service to Clevelanders, more than 80 years after the firm of Hubbell and Benes ceased operations in 1939.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.