The Edmund Fitzgerald: Remembering tragedy on the Great Lakes 50 years later

Monday, Nov. 10 will mark half a century since the S. S. Edmund Fitzgerald steamed into eternity in 1975, taking with it its entire crew of 29 men.

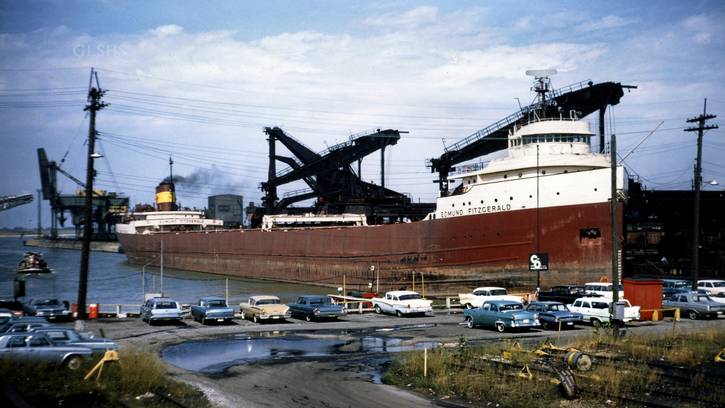

The story began 18 years earlier, on February 1, 1957. On that date, Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance placed an order with Great Lakes Engineering Works for a new cargo ship to be launched on the River Rouge in Detroit. The new ship was to be 729 feet in length, which would make it the largest vessel on the Great Lakes.

The plan was to lease the ship to the Columbia Transportation Division of Cleveland-based Oglebay Norton for a term of 25 years. Launched the following year, in 1958, the new ship's life began on a somber note—one of the spectators at her launch died of a heart attack.

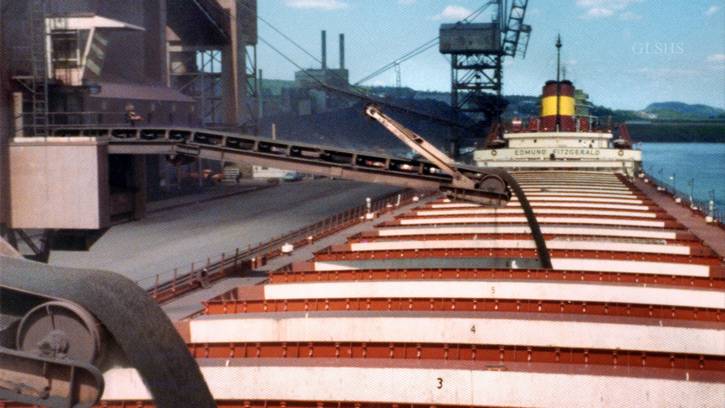

Named for an officer of the insurance company, against his wishes, the Fitzgerald settled into a long career of hauling coal and iron ore across the Great Lakes, typically from Superior, Wisconsin to a lower lake port in Detroit or Toledo.

A new ship like the Fitzgerald did not come cheap. At the time of her launch she was valued at $6 million, nearly $60 million in today's money.

Designated the flagship of Columbia Transportation, the Fitzgerald had unusually comfortable guest quarters. Guests traveling on ships like her were the people the company wanted to reward or impress. The general public could not buy a ticket.

The roundtrips the Fitzgerald made typically took five or six days and eventually covered a distance equivalent to dozens of trips around the world.

On the afternoon of November 9, 1975, the Fitzgerald left Superior, Wisconsin, carrying a load of taconite pellets headed for a steel mill on Zug Island near Detroit.

It began as a routine trip for the Fitzgerald, but that was about to change. The weather began to deteriorate, with winds gusting to fifty miles an hour and ten foot waves.

Another freighter, the Arthur M. Anderson, followed at some distance behind the Fitzgerald. This ship assisted with navigation since the Fitzgerald's radar was disabled by the storm. The harried captains maintained a terse dialogue which revealed that all was not well aboard the Fitzgerald.

The Fitzgerald's captain was 63-year-old Ernest McSorley, a veteran of almost 40 years on the lakes. He reported to Captain Jesse Cooper on the Anderson that the Fitzgerald had a couple of fence rails down. In plain English, this meant the two of the 5/8th inch wire ropes that formed the ship's rails on the main deck had snapped, suggesting great structural stress on the ship's hull.

Another strike against the Fitzgerald that night was the fact that she had been approved to carry considerably more cargo than her designers intended. This significantly reduced the vessel's freeboard—the distance from the waterline to the main deck.

The increased cargo also reduced the ship's reserve buoyancy, something that would have dire consequences on November 10, 1975.

As the day progressed, the already bad weather grew considerably worse. The wave heights and wind velocity both increased alarmingly.

What follows is conjecture. No one in the Fitzgerald's pilothouse survived to recount what happened, and the Anderson's crew was fully occupied with saving their own ship.

It is possible that the Fitzgerald wandered far enough off course to strike Six Fathom Shoal, an impact that went unnoticed in the commotion caused by the worsening storm. From that moment the ship's fate was sealed.

The hull began taking on a significant amount of water, all the time riding lower, and allowing massive seas across the deck. The Fitzgerald had no choice. It isn't as if they could heave to, go to anchor, and try to wait out the storm. The vessel continued on at an agonizingly slow pace—desperate to reach the shelter of Whitefish Bay, now less than 20 miles away.

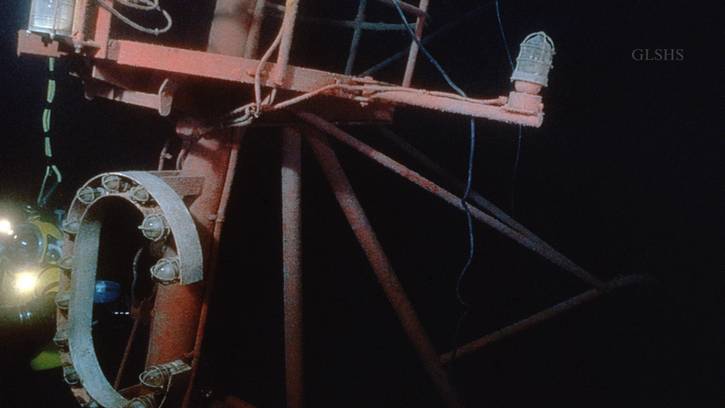

Shortly after 7 p.m., disaster ensued. A fatal combination of wind and waves drove the Fitzgerald's bow under the water. It did not stop until it hit the bottom 500 feet below.

The stern rose far out of the water, unsupported and subject to structural stress it was never designed to bear. Within just a few moments, the hull broke in half and lay broken on the lake bottom.

No one survived, and no bodies were ever recovered. Gordon Lightfoot's song, “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” was released the following year and sent the ship into legend.

The Great Lakes maritime industry was in shock. It had been 35 years since the freighters Anna C. Minch and the William B. Davock sank with all hands lost on the lakes in the deadly Armistice Day Storm of 1940.

The loss of the Fitzgerald signaled the end of an era. Ten years later, by 1985, many of her sister ships were gone, scrapped at Port Colborne, leaving once-crowded shipping lanes practically deserted.

The Fitzgerald lives on in scattered artifacts found in museums around the Great Lakes, the most notable being the ship's bell which can be seen at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum at Whitefish Point, Michigan. While at the museum, visitors can stand on the beach, look to the north, and try to visualize the last desperate hours of the Edmund Fitzgerald as she struggled to reach safety long ago in another century.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.