Safe at home: Shaping the future of healthy, affordable, and equitable housing

Housing issues in the city of Cleveland are characterized by a complex interplay of challenges that impact both residents and the overall community.

With a history of industrial decline, population loss, and redlining, the city faces a range of housing-related problems. The challenges include affordable housing shortages, deteriorating infrastructure, and housing segregation—which are exacerbated by economic disparities, racial inequalities, and the need for revitalization in some neighborhoods.

Moses Ngong, curator of Global Shapers ClevelandAddressing these issues is crucial for promoting social equity and sustainable urban development in Cleveland, making it a key priority for policymakers and community leaders in the region.

Moses Ngong, curator of Global Shapers ClevelandAddressing these issues is crucial for promoting social equity and sustainable urban development in Cleveland, making it a key priority for policymakers and community leaders in the region.

With that, Global Shapers Cleveland, a young professionals group sponsored by the World Economic Forum, and Black Environmental Leaders recently wrapped up its year-long series of conversations around environmental justice with a discussion on “Shaping the Future of Housing.”

Moses Ngong, curator of Global Shapers Cleveland moderated the conversation. The panelists include a number of thought leaders working to address the variety of housing issues in Northeast, Ohio.

Healthy homes

“What is [Collective Citizens Organized Against Lead]’s approach to addressing the quality of housing, the health of people living in homes, and the safety of Cleveland homes,” Ngong asked panelist Robin Brown, the organization’s founder and CEO.

CCOAL founder and CEO“We use a systematic approach in tackling what are our main issues keeping us unhealthy,” Brown responded, adding that what they are finding is that lead poisoning is the root cause of a lot of our ills and that they’ve discovered the housing stock in Cuyahoga County is “super old.”

CCOAL founder and CEO“We use a systematic approach in tackling what are our main issues keeping us unhealthy,” Brown responded, adding that what they are finding is that lead poisoning is the root cause of a lot of our ills and that they’ve discovered the housing stock in Cuyahoga County is “super old.”

“We have over 80% of our housing stock built before 1978,” she said, explaining that, in addition to lead, the housing materials in these homes are also hazardous—causing issues with asthma and other health disparities in underserved communities.

Collective Citizens Organized Against Lead (CCOAL) provides education to residents and advocates to change policy and laws.

Lynn Rodman of Slavic Village DevelopmentExpanding choices

Lynn Rodman of Slavic Village DevelopmentExpanding choices

Panelist Lynn Rodemann, director of the housing/healthy home initiative at Slavic Village Development (SVD), spoke about how SVD is addressing the lead issue.

“There is a very complicated intersection between having a rental unit that has poor quality, therefore exposing your children to lead, and finding quality housing you can afford,” said Rodemann.

So, in this space, she said SVD is really leaning into “resident empowerment,” by helping with conditions issues such as lead and connecting to resources particularly where residents can put their rent payments in escrow.

“That’s my main focus around lead right now because I think that’s a space that [isn’t] being served,” said Rodemann, adding that she thinks it’s a “direct injustice” for people to have to decide between being homeless or having their children exposed to lead—something she sees far too often.

“Our job as a development corporation is to find the gaps and step in where we can best serve, not to reinvent the wheel,” Rodemann continued.

Providing resources

CCOAL’s Brown said the way her organization is filling the gap is in the “humanity space,” thinking through how they can help the people navigate and lift them up to bring equity around housing as an environmental justice issue across the board.

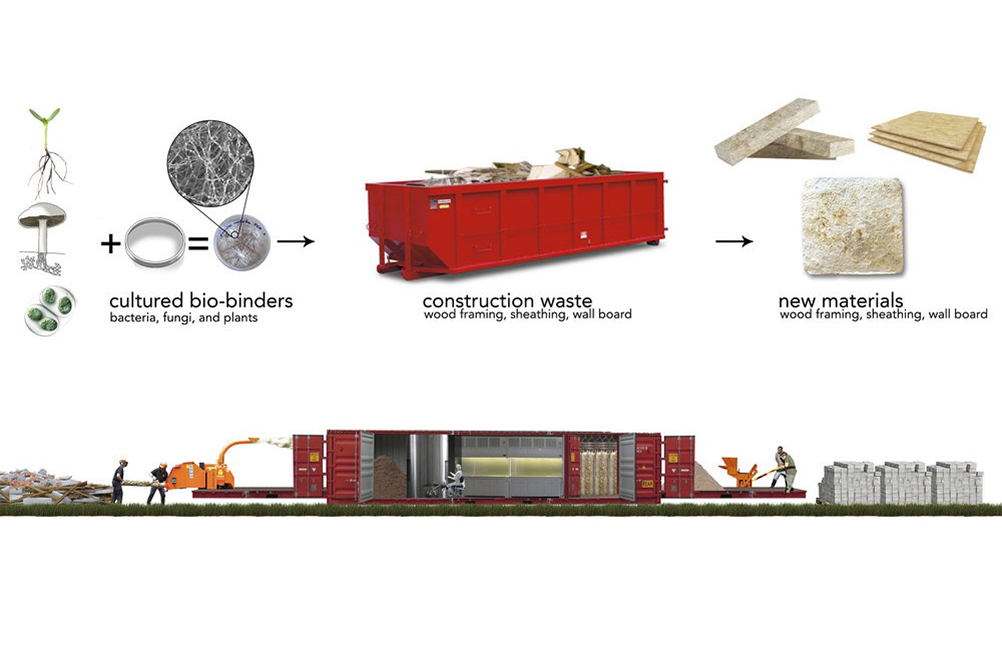

Chris_Maurer.jpgPanelist Chris Maurer, principal architect of redhouse studio in Ohio City, talked about “mycotectural interventions”—the process of incorporating biology to grow materials used in building.

Chris_Maurer.jpgPanelist Chris Maurer, principal architect of redhouse studio in Ohio City, talked about “mycotectural interventions”—the process of incorporating biology to grow materials used in building.

“We think the future is bio when it comes to building,” said Maurer of his work. “There are biomaterials that are being developed, not only with fungi but also with bacteria and algo substrates that are actually able to sequester carbon as you manufacture them.”

He explains how if the biomaterial is drawing down carbon monoxide as it’s growing, you can easily imagine a carbon-negative situation from that manufacturing—one of the reasons he says redhouse studio believes this is the future of housing.

“We have so much need to curb emissions and turn the dial when it comes to climate change,” said Maurer.

Much of what Maurer discussed is further into the future, but he did say, “We are already using the bio-performative aspect of things like bio-remediation,” he said.

For Cleveland, redhouse studio has a concept called “bio-cycler,” which will “almost literally” take a blighted house, put it into something like a meat grinder, and spit it out into a new “Palladian villa” that people can live in. This too, is a bit into the future, said Maurer.

Currently, redhouse studios can take those materials and, at a laboratory scale, put them through the process to inoculate them with microbes. The microbes are remediating the materials.

So, for example, with a lead-poisoned house, the lead dust can be remediated—even if it’s at a landfill, where it most likely ends up, said Maurer. “We’re talking about a system here that can break down some of the toxins in the environment.”

Josiah Quarles, director of NEOCHShelter issues

The fourth panelist, Josiah Quarles, director of organizing and advocacy at Northeast Ohio Coalition for the Homeless (NEOCH), talked about what his organization is doing to provide housing for the unhoused.

Quarles said the unhoused community locally, nationally, and even globally is growing due to a lot of economic factors and how the housing market is “implicitly inhumane” because it does not put “housing as a right,” but rather treats housing “as a commodity to extract profit.”

“We’re seeing that the population exploded here, particularly the unsheltered as well as families,” he said.

He’s also seen an increase in the private equity influence in the housing market, picking up portfolios of homes because they are relatively cheap.

With all of that, a lot of what NEOCH does is relational, said Quarles. They meet people where they are, and then connect them to resources available to help secure housing. NEOCH even holds their hand through the process.

“Having someone accompany them through that is really helpful,” he said.

They also organize tenants and residents together to seek redress and systems changes to get to the root causes of homelessness. “It’s not a personal failure,” Quarles added.

In the midst of Cleveland's housing challenges, the discussion led by Global Shapers Cleveland shed light on the diverse and innovative approaches being taken to tackle these pressing issues.

As the conversation emphasized, the detrimental effects of lead poisoning, aging housing stock, and access are disproportionately impacting underserved communities.

“This is the beginning of a conversation around housing that will continue in our city,” said Ngong.

This is the eighth story in a 10-part series designed to highlight how an intergenerational model is helpful in moving the needle in so many aspects of Cleveland as well as to uplift narratives of resilience and impact within the environmental justice space. Upcoming stories will spotlight different organizations working on environmental justice and climate change as well as capture the intergenerational voices working on these issues.