CMSD tries 'learning pods' to keep ESL students from falling behind in online schooling

On the fourth floor of a big building overlooking West 25th Street in Cleveland, a small group of young children sit beneath a ribbon of international flags—masks on, headphones in, spaced about six feet apart—in front of computers.

Save for the occasional murmuring of English and Spanish as staffers check on the students, it’s blissfully quiet and calm.

This “learning pod” at the Cleveland nonprofit Esperanza, Inc. is fulfilling an important need for a small number of Hispanic Cleveland Metropolitan School District students during the pandemic: A safe place, with reliable Internet, and a staff poised to help at a moment’s notice (in English or Spanish).

Esperanza, Inc, a Cleveland-based nonprofit that provides education programs to Hispanic children and adults.Victor Ruiz, executive director of Esperanza, says the learning pod—which has room for about 25 students—is an essential way to help English-language-learning students (commonly referred to as English as a Second Language or ESL students) who otherwise would be left behind during the pandemic.

Esperanza, Inc, a Cleveland-based nonprofit that provides education programs to Hispanic children and adults.Victor Ruiz, executive director of Esperanza, says the learning pod—which has room for about 25 students—is an essential way to help English-language-learning students (commonly referred to as English as a Second Language or ESL students) who otherwise would be left behind during the pandemic.

“We’re hearing of kids just not showing up to [virtual] school,” Ruiz says.

The calm environment and the ready aid from Esperanza staffers have helped seventh grader Efraniel Rivera, and her younger brother Dialeyshka get caught up on some of their work. It was a little hectic trying to learn at their small near-West Side Cleveland apartment, with their four-year-old brother, their mother and their uncle all staying under one roof.

“It was hard to hear what the teacher was saying,” Efraniel says.

The learning pod at Esperanza is one of 24 locations in Cleveland—funded by the Cleveland Foundation and United Way of Cleveland—where almost 800 CMSD students go daily to do their virtual-only classwork. Homeless students, poor students and English-language learners are struggling the most with online-only work.

Esperanza is also one of only two such pods that focus ensuring English learners do not fall behind on their education. Online learning during the pandemic has been difficult for the most vulnerable populations of students in the U.S.—especially poor students of color and those learning English as a second language.

A recent study from the Migration Policy Institute (MPI)—a Washington, D.C.-based think tank for liberal immigration policy—found that back in spring 2020 when school districts first closed their doors, many English learners either weren’t logging in, or couldn’t.

In Chicago, slightly more than half of English learners were logging in at least three days per week, while at Los Angeles Unified School District, less than half of English learners participated in remote instruction, 20% lower than their native-English-speaking peers.

At CMSD meanwhile, the average daily log-in rate during fall 2020 was close to 64%.

Senaida Perez, a family engagement and student support coordinator for CMSD, says many English learners are falling behind because their caregivers (usually parents and grandparents) often can’t provide the help they normally get in the classroom. Either those caregivers are working—and therefore aren’t present when their students run into trouble with the online learning software—or they simply don’t have the knowledge to help them.

Many parents and grandparents of English learners have limited English proficiency themselves. Some also don’t know much about computers or the Internet, Perez says.

“As soon as there’s a glitch, [parents] don’t know what to do, and they just let it go,” she says. “So, then the kids get behind.”

Esperanza does have adult literacy and digital literacy programs that can help those caregivers, but the organization only has so much space for those classes.

Melissa Lazarin, the co-author of the MPI study paper, says many school districts are trying to figure out how best to prevent English learners from falling further behind during remote-only learning. But there’s no clear single solution, Lazarin says.

The main barriers, though, are clear, according to the paper: Many immigrant families don’t have access to decent Internet; parents have limited capacity to help their children at home; and there’s a lack of resources and training for teachers to improve the remote learning experience of English learners.

A small group of Hispanic CMSD students attend their virtual-only classes inside the Cleveland nonprofit Esperanza, Inc’s offices.Students aren’t logging in and are missing assignments

A small group of Hispanic CMSD students attend their virtual-only classes inside the Cleveland nonprofit Esperanza, Inc’s offices.Students aren’t logging in and are missing assignments

The CMSD learning pods aren’t the only such support available in the Greater Cleveland area.

Recognizing some of the challenges students face with online learning, the Boys and Girls Clubs of Northeast Ohio pivoted in August 2020 to run 18 different “ClubSmart Centers” in the region. These are physical locations where children can come during the school day to be supervised. The centers are similar to the CMSD learning pods but are open to any student.

Two of those centers—at the Riverview Welcome Center and the City Life Center. 1701 W. 25th St. in Cleveland—serve a majority Spanish-speaking population, says Boys and Girls Clubs of NEO spokesperson Amy Skolnik.

Alex Rivera, club director at the Riverview site, says the learning center has been a boon for both caregivers and English learners alike.

The lack of in-person support, which students would get when in a normal classroom, coupled with a learning portal that can be confusing to both caregivers and students adds up. “We have seen some of our members come in with 100-plus assignments that they haven’t done yet,” Rivera says.

With work and time, Rivera’s staff (all of whom speak Spanish) has been able to steadily catch those students back up, he says.

The CMSD learning pods are showing great promise too. According to an analysis conducted by United Way of Greater Cleveland, about 98% of parents with children attending the learning pods agree that the pods “truly helped during this time of virtual learning, with their students being able to get the support they need,” says Katie Connell, a United Way of Greater Cleveland spokesperson.

Nancy Mendez, vice president of community impact at United Way, says the CMSD learning pods similarly saw a large number of students coming in with lots of assignments they hadn’t completed yet.

Another important feature of both the learning pods and the ClubSmart Centers—lunch for the students, many of whom are from families struggling financially, or are homeless.

Despite these early signs of success, Lazarin says there’s not much research yet to show whether learning pods in general have helped English learners keep up with their peers during remote-only learning. Her paper does note that partnerships between schools and trusted community partners—like Esperanza and the Boys and Girls Clubs—are key in attempting to overcome barriers.

However, there’s only so much space for students at the learning pods because of the need for social distancing and limited funding. The Boys and Girls Clubs of Northeast Ohio is currently serving between 350 and 400 students on any given day through the ClubSmart centers, Skolnik says, and only a small fraction of those students are English learners.

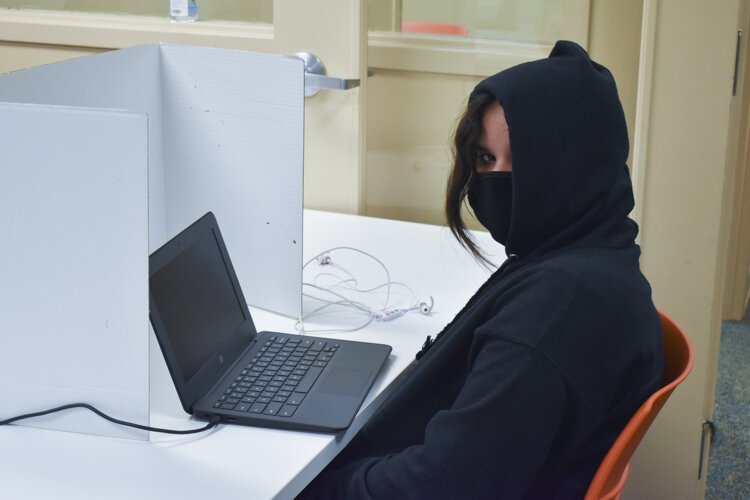

One of the CMSD students does his classwork at a learning pod inside Esperanza’s offices in Cleveland.Similarly, only a small portion of the CMSD learning pods are devoted to English learners (CMSD has about 5,000 English learners total, 89% of whom are Spanish-speaking). Plus, both the CMSD learning pods and the ClubSmart centers are mostly geared toward students in grades K-8, the students who likely have the greatest need for help.

One of the CMSD students does his classwork at a learning pod inside Esperanza’s offices in Cleveland.Similarly, only a small portion of the CMSD learning pods are devoted to English learners (CMSD has about 5,000 English learners total, 89% of whom are Spanish-speaking). Plus, both the CMSD learning pods and the ClubSmart centers are mostly geared toward students in grades K-8, the students who likely have the greatest need for help.

For the two sites that serve the Latino community, there are waiting lists for students to get into the learning pods, Mendez said.

It’s also not cheap to keep the learning pods going, which are spread across 24 different sites and need staffing for each. And that funding ends soon.

It cost $1.22 million to run the CMSD learning pods from early September to winter break in December, and the latest extension—expanding their usage through Feb. 5—will cost about $300,000. It could cost almost $1.7 million to extend the learning pods through the end of the school year (this funding has not yet been secured), Connell says.

Despite the help from the learning pods, CMSD is still struggling with lagging attendance numbers, far worse than in normal years. The average daily login rate for students in grades 3-12 stands at a distressing 63.9% (63.7% for English learning students), according to CMSD data, which tracked login rates to the school district’s “Schoology” system from Sept. 3 to Dec. 11.

There are a few caveats to the data: It doesn’t track whether students go back into the system later to complete assignments they missed; and the data only represents log-ins, not individual students, so it’s not clear if it shows a population of students consistently not logging on.

Still, it’s a statistic that has raised alarm bells for advocates. The education news website The 74 Million reported that of CMSD’s 36,900 students, about 28,200 attend classes on a typical day.

While data provided by the school district doesn’t suggest much of a difference in absentee rates for English learners versus other students, it’s still concerning because, according to the Migration Policy Institute study, these students are typically 1.2 times less likely to be chronically absent from school.

Want to sign your child up for one of the CMSD Academic Learning Pod Initiative programs? While most of the learning pods are likely at capacity, you can check with the individual learning pod operators to see if they have room or a waitlist. See a list of providers here.

What other help is available?

Jose Gonzalez, executive director of multilingual multicultural education at CMSD, says families of English learners at CMSD have plenty of things on their plate to deal with. Stewarding their children’s education is another added burden.

To help, the district has piloted several new measures, in addition to its normal support services. The district has put translated materials on how to access and operate its online learning portals on its website. There’s also a helpline available in multiple languages for parents struggling with the technology, plus an in-person option, where caregivers and their students can go to their school building or another location to talk to somebody in person, Gonzalez says.

The district also recently began sending refugee students who are struggling to a “learning lab” operated by Refugee Response. Those students are brought in (with transportation provided) for two hours after school each week to get intensive, in-person help from Refugee Response staff.

Naila Paul, director of education at Refugee Response, said the learning lab is starting small—just a few families per week—but it’s been helpful, especially since transportation to the lab is provided. She says many immigrant families don’t have a car, which can prevent them from bringing their kids to the learning pods. She said she thinks the lab has been helpful. Often, these students and their families are struggling to navigate CMSD’s learning portal.

“You look at the [online learning] portals for some of the kids…and it says ‘any overdue assignments.’ That list just keeps scrolling, it’s endless,” Paul says. “So, we looked at that and said, ‘let’s start with today.’”

Perez is also one of two CMSD family engagement coordinators who is just a phone call away when families run into trouble. She helps parents who are having trouble logging in, or with anything else, including avoiding eviction and feeding their families.

Ibis Maldonado, youth program coordinator at Esperanza, works with CMSD students each week to ensure their online learning is going as smoothly as possible.Gonzalez noted that Cleveland has a “huge digital divide,” meaning people do not have access to reliable Internet and computers. That impacts immigrant families especially. Recognizing that, the school district and its partners have provided thousands of devices and wifi hotspots to families.

Ibis Maldonado, youth program coordinator at Esperanza, works with CMSD students each week to ensure their online learning is going as smoothly as possible.Gonzalez noted that Cleveland has a “huge digital divide,” meaning people do not have access to reliable Internet and computers. That impacts immigrant families especially. Recognizing that, the school district and its partners have provided thousands of devices and wifi hotspots to families.

Back at Esperanza, Ivis Maldonado, youth program coordinator, said that while the support the learning pod provides to students does seem to be helping them get their schoolwork done, there’s a missing piece.

“It’s those social-emotional skills” that students are not developing while away from their peers in traditional in-person classroom settings, Maldonado says.

Zulayka Ruiz, director of programs at Esperanza, said the nonprofit brings in Cleveland State University students once a week to mentor the students, which provides a little of that social-emotional experience. But it’s not the same as daily interactions with their fellow classmates.

Lazarin, of the Migration Policy Institute, said the best thing for these students would be to get them back into the classroom as soon as it can be done safely. She suggest in the paper that states and school districts prioritize English learners for hybrid or in-person instruction.

“These students need access to a language-rich environment and a lot of that can’t necessarily be accomplished online,” Lazarin says.

This story is sponsored by the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative, which is composed of 20-plus Northeast Ohio news outlets including FreshWater Cleveland. Conor Morris is a corps member with Report for America. Claudia Longo, a writer with La Mega Nota, contributed to this story.

Editor’s note: Reporter Conor Morris’ salary is partially funded by the Cleveland Foundation.