Keeping it clean: Metroparks embraces green infrastructure to naturally treat stormwater runoff

For Northeast Ohioans, human impact on the earth's water supply hits very close to home. After all, we're right next to the largest fresh water lake system in the world.

The Cleveland Metroparks is well aware of the impact on Northeast Ohio’s water supply, and in 2023 the parks system is embarking on four green infrastructure projects to keep our drinking water clean and potable. Per preliminary estimates, the work is slated to cost $970,00, and the organization has garnered approximately $824,000 in grants to cover the funding.

Mother Nature's process for cleaning all that water is pretty simple: rain cascades down from the sky and splashes through leaves and vegetation en route to the ground. There, a humble system of soil, sand, and other organic materials act as a filter before the rain becomes part of the ground water and eventually makes its way back to Lake Erie via creeks, streams and rivers.

Bioswale illustration by Doug Adamson, RDG Planning & Design, provided by USDA-NRCS in Des Moines, Iowa

Bioswale illustration by Doug Adamson, RDG Planning & Design, provided by USDA-NRCS in Des Moines, Iowa

It's a brilliant and economic system. Unfortunately, every time a drop of rain hits a manmade impervious surface (think parking lots, roofs, and roads), that system is essentially interrupted.

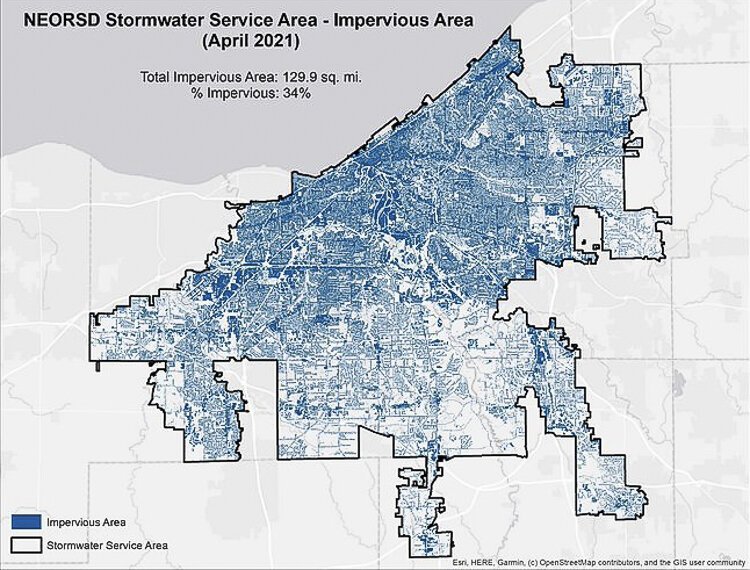

Those interruptions add up quickly—and to our collective detriment. To quantify, 34% of the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District's (NEORSD) storm water service area is covered in impervious surface. That's a staggering 130 square miles. And when a raindrop lands on one of those surfaces, it sluices over oily asphalt and grimy concrete and gets reintroduced to natural bodies of water via our manmade stormwater system of pipes and culverts and drains.

The more impurities humans introduce at the beginning of the process, the more we humans must clean out of that water before it flows from your kitchen tap.

“Anything we can do to improve water quality going into Lake Erie is going to improve our drinking water source,” says Jenn Grieser, the Metroparks' director of natural resources. “The cleaner it is, the less money [the Cleveland Division of Water] needs to spend on making sure it is up to our drinking water standards.”

“The more polluted it is, the more it costs at the end of the tap,” Grieser continues. “That's really what it comes down to.”

Projects like the one in the Bedford Reservation will facilitate the capture of millions of gallons of storm water runoffBuilding green

Projects like the one in the Bedford Reservation will facilitate the capture of millions of gallons of storm water runoffBuilding green

One way to address the problem is to treat the runoff naturally. To that end, the Metroparks is launching into 2023 with four subtle-but-mighty green infrastructure projects at three areas in the Lakefront Reservation (Edgewater Park, the Nature Preserve near the East 72nd Street fishing area, and Euclid Beach) and Dunham Park in the Bedford Reservation.

The projects will facilitate the capture of millions of gallons of storm water runoff, primarily from parking areas, including those that currently discharge directly into Lake Erie.

How do green infrastructure systems work? They aim to collect and sustainably treat impervious surface runoff by diverting it into bioswales, which then treat the water much the way Mother Nature does. Per this concise introduction to bioswales, these simple green and natural features are “typically a vegetated channel that can be used in place of a ditch to transport stormwater runoff from streets, parking lots and roofs.”

Benefits include:

• Receiving and slowing runoff generated during small to medium storms, allowing it to infiltrate into the ground rather than directly discharge through a pipe or concrete channel.

• Providing some flood storage.

• Filtering, trapping, and removing contaminants such as nutrients, heavy metals, harmful bacteria and pathogens, sediment, oils and grease, etc.

But cleaner water is just one benefit. "Something that's important is a lot less water is coming out in the end,” notes Grieser of green infrastructure effluent. “It's not just coming out cleaner, but it's a lot less [water]. That is the primary driving force of these storm water practices. It's water quantity control. We're reducing the runoff that impervious surface creates.”

It doesn't end there. “There's a whole slew of other benefits,” says Greiser, noting the impact extends to ecosystems surrounding wildlife, particularly those associated with birds and insects as well as their habitats.

Further reading: Metroparks, partners quietly exalt and nurture the fragile Cuyahoga.

The green infrastructure plan

At Edgewater, the work will include the addition of two 5,400-square-foot vegetated bioswales for a total of 10,800 square feet of new green infrastructure. While a final design is pending, the bioswales will utilize an existing piping system throughout the parking lot that currently discharges to the lake. That water will instead be rerouted to the bioswales for natural treatment.

"We'll be routing every drop of rain that hits the asphalt into one of these [bioswales] on either side [of the parking lot]," says Metroparks' director of construction Jim Rodstrom, adding that the system is not perfect, but a vast improvement over simply releasing it into the lake. Work is estimated to cost $375,000.

Edgewater Beach House green infrastructure improvements

Edgewater Beach House green infrastructure improvements

The work at the Cleveland Lakefront Nature Preserve, estimated to cost approximately $170,000, will be in the parking lot adjacent to the Metroparks' administrative building and will include constructing three vegetated bioswales totaling 4,200 square feet to treat runoff from pavement as well as the restroom and building roofs.

"Right now all the water runs to sewer locations," says Rodstrom, "and we're simply removing the catch basins and putting in green infrastructure."

Grant funds totaling $522,500 will finance both projects, which will capture and treat nearly 5.4 million gallons of storm water annually. The Sustain Our Great Lakes Program is funding $272,500 of that sum; and the Ohio Department of Natural Resources' H2Ohio initiative is providing $250,000. While final costs will depend on design and bidding details, estimates for the projects total $545,000.

Any funding shortfall between the grants and actual costs will be covered by the Metroparks—either monetarily or with in-house, in-kind work/service. Construction for both projects is estimated to start after Labor Day 2023, with additional details becoming available as design continues.

At Euclid Beach, plans include the removal of more than 16,000 square feet of pavement and the addition of more than 10,000 square feet of green infrastructure, including bioswales and catchment space on the beach.

“Right now, there's so much flow that it overwhelms the beach and we have to go through and repair the beach every time [a significant rainfall] happens,” says Rodstrom. The improvements are expected to eliminate about 2.5 million gallons of untreated runoff into Lake Erie.

Euclid Beach parking lot green infrastructure improvements

Euclid Beach parking lot green infrastructure improvements

A $200,000 grant from the Great Lakes Sediment and Nutrient Reduction Program will fund the bulk of the Euclid Beach work, which is estimated to total $300,000. The Metroparks will also augment grant funds as needed when the finalized totals are known. Construction should take about three months and start in mid-2023.

Plans are still under development for Dunham Park, but Rodstrom reports, “We're going to reconfigure the entrance, but also provide green infrastructure that will reduce our [storm water effluent] volume and also [improve] water quality.”

He notes that will include bioswales and dry detention basins (essentially holding areas for excess storm water). The road modifications will add dedicated pedestrian and bicycle access. A $101,478 grant from the Ohio EPA's Nonpoint Source Pollution Control Program will serve as primary funding for the $125,000 project, which is estimated to capture and treat more than a half million gallons of water annually. Bidding is slated for spring 2023. Construction is expected to go on for 45 days.

The big picture

These four upcoming projects join a long and vibrant list of green infrastructure efforts across the park system. They range from highly visible and lush vegetated bioswales like those in the parking lots for the Chalet and Merwin's Wharf, to efforts deeper within the Emerald Necklace, such as improvements at Brookside Reservation—which include approximately 11,000 square feet of bioretention that prevent more than two million gallons of stormwater from discharging directly into Big Creek.

Completed in 2020, the project goes one step further. The bioswales are outfitted with equipment that monitors water flow, quality, and quantity. Such ability is new for the Metroparks.

“We've never had the opportunity to monitor their actual performance,” says Rodstrom of the green infrastructure scanning equipment.

“Being a park district that's over 100 years old, practices have changed, and we are modifying the environment to respond to what we're learning,” adds Greiser. “That's what adaptive management is.”

Properly treating runoff from impervious surfaces, adds Rodstrom, is one of those things the park system is learning how to master.

“There's a balance in there somewhere,” he says.