The fate of Euclid Beach Motor Home Park

When Western Reserve Land Conservancy (WRLC) in December 2021 purchased the 28.5-acre Euclid Beach Mobile Home Park on North Collinwood’s Lake Erie shoreline, WRLC senior vice president and director of thriving communities Matt Zone assured the approximately 139 residents with 150 mobile homes on the property that the purchase was made to save the property from a Dallas-based developer who planned to build high-rise apartments.

Zone and Cleveland ward 8 councilperson Mike Polensek assured the residents that the next steps would focus on brainstorming sessions to figure out how the land could best serve the residents and the larger Cleveland and Collinwood communities.

one promised compassion and said there would be no evictions or changes for at least the first year. WRLC hired a park manager to perform maintenance on the park during this period.

WRLC paid $5.8 million for the property—becoming the owner of largest privately-owned parcel along North Collinwood’s lakefront.

More than a year later, after assessments, community meetings, discussions, and planning by WRLC, Cleveland Metroparks, Cleveland Neighborhood Progress, Greater Collinwood Development Corporation, the City of Cleveland, and residents, the group has developed a Euclid Beach Neighborhood Plan.

Proposed park areaIn 2021, Zone called the chance to develop part of the lakefront a “once in a generation opportunity,” and he vowed to make sure the planning was extensive and took everything into consideration—including the current residents on the property and the potential for the Cleveland community.

Proposed park areaIn 2021, Zone called the chance to develop part of the lakefront a “once in a generation opportunity,” and he vowed to make sure the planning was extensive and took everything into consideration—including the current residents on the property and the potential for the Cleveland community.

The plan, released in early February, will close Euclid Beach Mobile Home Park, giving residents until September 2024 to vacate the property. The 28.5 acres will then become part of the Cleveland Metroparks, consolidating with the existing nearby Metroparks beaches and marinas.

The current park property is located between Euclid Beach Park to the west and Villa Angela Beach and Wildwood Marina to the east—all of which are managed by the Cleveland Metroparks. The Cleveland Public Library Memorial-Nottingham branch, housed in the former Villa Angela Academy, sits on 18 acres near the property’s southern entrance.

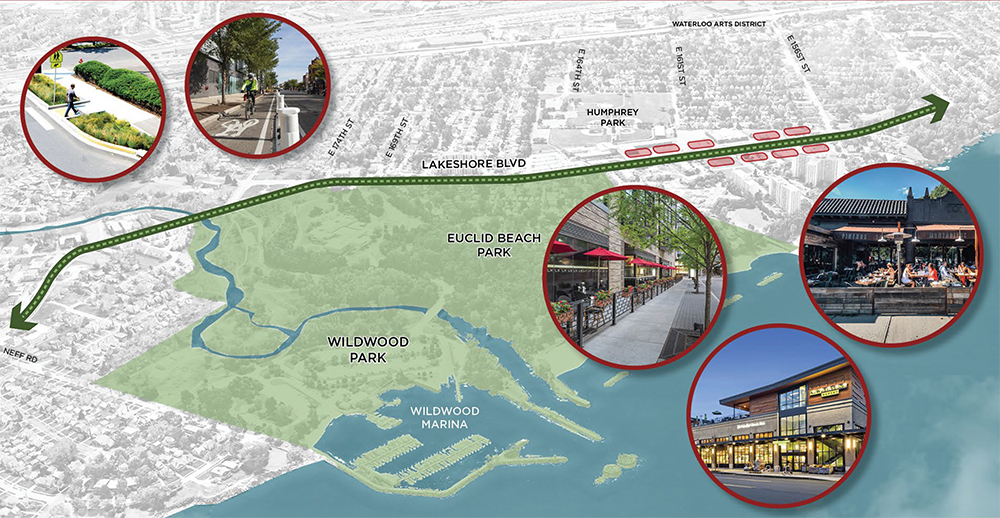

The Euclid Beach Neighborhood Plan is designed to unify the surrounding beaches and marina, the Metroparks Euclid Creek Reservation, the Villa Angela woods, and a revitalized Lakeshore Avenue.

The plan calls for infrastructure improvements on Lakeshore Boulevard that include installing underground utilities; creating two traffic lanes, a dedicated turning lane, and a buffered bike lane along Lakeshore; and a new cityscape that includes outdoor dining on large, landscaped sidewalks.

While the organizers and many community members are excited about the plan to further develop the city’s lakefront and improve the Lakeshore Avenue area around the beaches, some Euclid Beach Mobile Home residents and their supporters are upset at the decision.

Last August, some of the Mobile Home Park residents formed the United Residents of Euclid Beach (UREB) union. The union was meant to ensure residents could stay in their homes or receive adequate compensation for their homes if they must leave.

On March 28, with the backing of Northeast Ohio Coalition for the Homeless (NEOCH) and the Legal Aid Society of Cleveland, UREB presented a petition signed by 558 people to WRLC, asking that the group reverse the decision to close the park and explore alternative solutions—namely, set aside a portion of the land near Lakeshore Boulevard where residents interested in staying could relocate their homes.

Park Residence Heather Malone alongside Gillian Pater-Lee from NEOCH present a representative from WRLC with signed petitions from United Residents of Euclid BeaThe petition stated, in part:

“Euclid Beach Mobile Home Park residents desire to protect and preserve their homes, lives, memories and community. The mobile home park is a microcosm of America, like any other neighborhood. We, as concerned citizens and neighbors, stand in support of UREB in their fight to keep the mobile home park open and residents in their homes.

We ask that WRLC and its partners:

- Reverse their decision to close the Euclid Beach Mobile Home Community entirely.

- Sit down with park residents to hear their ideas and explore alternative solutions (such as, reducing the park’s size to accommodate public access to the lake, and/or a partnership with ROC USA that would result in resident ownership of the park); and

- Allow for good faith, humane, respectful, and cooperative negotiations by immediately sharing with UREB all financial information, feasibility studies, engineering studies, and other documentation and records regarding the mobile home park and the Euclid Beach Neighborhood Plan.”

The east end of the property once had Euclid Beach amusement park employee housing and land for temporary employees to set up their trailers. The parks operated from 1895 to 1969.

“The [Dudley S.] Humphrey family that [managed the park] then determined they needed to generate some cash flow and revenue,” explains Zone. “So, they allowed this land to transition into a temporary short-term use in mobile home community. And it's kind of morphed into what you have today.”

In fact, Euclid Beach Park and Lakeshore Boulevard were the center of attraction in North Collinwood in the early 1900s.

“Streetcars used to come in and drop people off at the park and a lot of really cool things happened there,” Zone says. “President Kennedy spoke there. The former Cleveland Indians and Spiders played in professional baseball leagues at the park. It's where people came to recreate and touch the water's edge.

“It's where people came to dine and there was an old bath house—people would come there because there was not a lot of working plumbing in the early 1900s,” Zone continues. “There were several cottages that people could rent on site. There's an old carousel that's now the Western Reserve historical site, and an old ticket booth that we plan on renovating.”

From 1949 to 2012, various elected officials, government agencies, and organizations have created five different plans to join the beaches and parks along the North Collinwood lakeshore—many of which suggested moving or eradicating the Euclid Beach Mobile Home Park.

“What all of these studies have in common is, over the last 75 years all have attempted to consolidate and unify the lakefront park,” Zone says. “We have just now completed a sixth planning process, and [consolidation] was the recommendation. Cleveland has a problem that it does planning work and then it never implements the plan.”

Park resident Heather Malone speaks at the United Residents of Euclid Beach rally in downtown Cleveland on March 28th, 2023Angry and concerned

Many of the 139 residents who remain in the park are upset that they are about to lose their homes. While the residents own their mobile homes, they lease the land.

Kaitlyn Gumbish and her husband discovered Euclid Beach Mobile Home Park six years ago and decided to buy a trailer. “We had no idea this was even there,” she recalls. “We figured it was there for so long, it would be here for a while.”

Gumbish paid $4,000 for the trailer in 2016 with plans to renovate it. “We were already in mid-renovation, had spent a couple thousand dollars, and stripped it to the studs in October 2021,” she recalls. “In November, the furnace went out, and [so did] the electrical and plumbing.”

Gumbish says they were thinking about selling the trailer in 2019 for $11,000. When the news broke of WRLC plans for the property, she said it was time to leave.

She sold the trailer to WRLC last month for $2,600. “It was worth way more than that,” she says, noting that she still hadn’t received the money 21 days after moving out. “It’s awful. They’re really treating people terribly.”

Gumbish says many of the residents are low income and have other challenges. “There are a lot of characters in that park and they’re all trying to do the best they can,” she says.

Anthony Beard has lived at the park for 16 years. “I was going through a divorce and had to find a place for my children and I to reside in 2007,” he recalls. “My parents used to live [nearby] in the Euclid Beach Villa apartments, and I made a wrong turn into the park. I saw signs saying ‘available.’”

Beard says he decided to buy a trailer in the park. “It’s been 16 long years,” he says. He accepts that WRLC is closing the park, but he says he is frustrated with the way things are being managed.

He says he was told the mobile homes are moveable, but safety standards prohibit mobile homes made before 1980 from being moved.

Beard’s biggest grievance is with the way the park has been managed since WRLC bought it. He says he knows the infrastructure in the park is in bad shape, but he says that’s not an excuse for the lack of maintenance.

“Everyone understands the infrastructure is bad—it’s old,” he says. “The previous owners were working on it every single day. Since January, I can count on my fingers how many times the manager has been in the office. I can see her office from my kitchen window, and she’s been there less than 10 times in 2023.”

Saylor says the previous owner left WRLC to deal with 35 years of deferred maintenance at the mobile home community, and the organization immediately went to work on repairs after purchasing the property.

“Our first action was to provide each unit with a wireless water meter, so residents were no longer being charged for water that leaked into the dilapidated underground pipes and they only paid for what they used,” he explains. “We paid to relocate an overwhelming feral cat population; we filled potholes; removed dead trees; planted flowers and tended to other landscape problems.”

“For six months prior to us taking ownership in December 2021, there was no office manager,” continues Saylor. “The park was purposefully being run into the ground as the previous owner held little concern for the well-being of the tenants as he wanted to sell to a developer who would have immediately [evicted the tenants]. “Once we purchased the property, we hired an accomplished mobile home community management company and hired a full-time on-site property manager with more than a decade of experience.”

Anthony Beard a current Euclid Beach Mobile Home Park residentBeard doesn’t trust anything he’s been told, given the problems he’s had. “Landlords have to give 180 days’ notice [of eviction] by law, but WRLC said we have until September 2024,” he says. “I’m suggesting to residents that they have a plan A and plan B in pace, because they could go back on their word.”

“That is precisely why we have given the residents three times the statutory requirement so residents will have ample time to find other housing options,” retorts Saylor. “What is not required by law is the amount of housing resources, social services, and eventually a fair compensation package to assist residents in their move that we have consistently provided.”

Beard’s ideal solution: “Sell us the land, and we’ll take care of the rest,” he offers. “They’re telling us, ‘you guys couldn’t afford it.’ Says who?”

In October, Beard attended a webinar hosted by ROC USA—neighborhoods of Resident-Owned Communities run as a cooperative.

Other residents have suggested WRLC section off a bit of the property by Lakeshore Avenue for the mobile homes and let those who want to remain at the park simply have a smaller footprint.

NEOCH’s director of organizing and advocacy Josiah Quarles says they first got involved when WRLC bought the land because of the worry that many of the Euclid Beach Motor Home residents were in danger of experiencing homelessness when the park closes.

“Whenever there is displacement, there is a possibility of people falling through the cracks and becoming unhoused,” he explains. “We really wanted to make sure that didn't happen. At the same time, we were launching upstream work in housing organizing, tenant organizing and trying to do that work in those spaces to prevent people from falling into homelessness.”

Quarles says NEOCH brought in Legal Aid to help address residents’ concerns and find out what they, as a group, wanted to happen.

He differentiates resident-only meetings, at which the tenants shared their true concerns, from the neighborhood meetings held by Cleveland Neighborhood Progress, where he says broader plans and goals were discussed.

In the end, Quarles says many residents felt left out of the planning process, and they really didn’t know the details until they were announced on Feb. 9.

Ultimately, Quarles says the residents who had not given up hope still thought there could be a compromise.

“[They wanted] a substantially shrunken footprint that moves folks away from the lake, which allows the park to really connect along the lake and would center the housing closer to the street,” Quarles explains. “There would need to be some capital improvements which could be facilitated through some low or no interest loans as well as potentially some other funds that could be held within a land trust that would be established.”

Though he concedes that many of the motor home park residents are elderly, disabled, or low-income, he says there are residents who were willing to invest. “Residents would then buy into that [land trust] and they would take on the loan payments, [which] would be spread across all of the residents,” he suggests. “They would basically take on a mortgage, which would slightly increase their monthly payments but secure their housing forever.”

Cigorni Sapp owns two mobile homes in the park but decided to move out more than two months agoAnother opinion

Cigorni Sapp, who owns two mobile homes in the park, decided to move out more than two months ago, but her mother chose to stay in her home for now.

She attended the resident meetings and steering committee meetings with WRLC and the partners from the beginning and, with a background in carpentry and maintaining two homes at the park, she says she thinks the Euclid Beach Neighborhood Plan makes sense.

“I think it’s a viable plan,” Sapp says, adding that the needed infrastructure work and other repairs needed in the park just don’t make a good argument for keeping the mobile home park.

“As far as what Western Reserve Land Conservancy wants to do, it actually will be better than what a private [company] would do. It needs a lot of work.”

Sapp, who is on the board of the Ohio Manufactured Homes Association, is a graduate of East Tech High School, is a former Cleveland Police officer, and just finished eight years in the Air Force, still live nearby and says she hopes everyone can make a smooth transition. “I’m trying to carry my weight, keep my nose clean, and keep a good record,” she says. “It’s not your typical evictions—you and your house have to go.

She says many of the current residents are disabled or senior citizens and are not equipped physically or financially to make the types of repairs needed. Additionally, she says many residents don’t have leases or titles to their mobile homes.

“The idea of tenants getting together to fix the park, most of them don’t have the money to take care of their home or themselves,” she says. “So, to get $1 million or $5 million together to be tenant-owned or be a privately run park just isn’t feasible. Some people don’t even have leases or titles to their houses. If you can’t manage your own property now, there are going to be bigger issues trying to take them on later.”

As far as WRLC’s work, along with EDEN, Inc. and Cleveland Neighborhood Progress, Sapp says she feels the organizations have done a good job in keeping people informed and offering assistance. “I think they did a great job and there are a lot of great options—and time to prepare for it,” she says. “It’s not like anything was hidden. They were very transparent.”

Although Sapp no longer lives at Euclid Beach Mobile Home Park, she says she would like to see a new park come into the Collinwood area. “This is the only one in Cleveland,” she says. “The closest one is in Brook Park. I love my manufactured home.”

Beyond repair

When United Residents of Euclid Beach presented the petition to WRLC in March, WRLC’s director of communications and public relations Jared Saylor accepted the group’s petition.

While the groups presenting the petition claim 558 signatures, Zone argues that the number is misrepresented—with only 12 signatures from tenants of the mobile home park.

“One thing I think I can safely [say that we] do agree upon with NEOCH and the 12 residents of the EBMHC partnering with them is [we need] to prioritize the needs of the residents and treat them with fairness and respect,” Zone wrote in an email. “We continue to be fully committed to that promise. Cleveland needs this project. And the residents need to be taken care of. We understand this is a big step and will continue to be fair and compassionate.”

Zone says there is no way to keep the park open, create a smaller footprint for a few residents and their trailers to remain on the property, or make the necessary infrastructure repairs to keep the entire park intact.

“The reality is, given the age and condition of most of the mobile homes, they can not be moved,” he says. “Even a smaller footprint would cost millions of dollars, which would make it unfavorable for the tenants to live there…. Rent would increase 10-fold. The park is going to close down.”

Within six months of WRLC owning Euclid Beach Mobile Home Park, there were water main breaks every monthFor example, Zone says within six months of owning Euclid Beach Mobile Home Park, there were water main breaks every month and WRLC spent $35,000 on repairs in February alone. “The infrastructure wasn’t built to commercial code, and the [previous owner] was using a mom-and-pop plumber to accommodate all the units,” he explains.

Zone emphasizes that WRLC and the partner organizations have been working with the residents since WRLC took ownership and have kept them informed the entire time. “It’s been a year-and-a-half, which is triple the statutory time,” he says. “We will continue to work with the tenants to meet their needs. EDEN is working with all tenants about their unique needs. We met with them on-site. I was there—we talked and shared with everyone. We’re not hiding from this issue. We are going above and beyond.”

Working with residents

WRLC is working with local housing providers to help find acceptable housing options for the tenants, converting the Euclid Beach property “for the greater public good.”

Additionally, Zone says they are creating a financial compensation package for tenants and owners to help them with the transition. That package should be ready by May.

“EDEN’s outreach and stability specialist and our staff will work with each resident to ensure they have a clear understanding of the compensation, resources, and services that will be made available to help them in this transition,” Zone says.

Proposed revitalized Lakeshore BoulevardAndrew Sargeant, director of open space and planning for Cleveland Neighborhood Progress (CNP), says his organization was never directly involved with the tenants of the park, but got involved with the planning to see what the larger development plan could look like to Collinwood as a whole—particularly after the neighborhood’s only grocery store closed last April.

Proposed revitalized Lakeshore BoulevardAndrew Sargeant, director of open space and planning for Cleveland Neighborhood Progress (CNP), says his organization was never directly involved with the tenants of the park, but got involved with the planning to see what the larger development plan could look like to Collinwood as a whole—particularly after the neighborhood’s only grocery store closed last April.

“We were essentially working with outside stakeholders, including the city and some other folks that were listed in our stakeholder group, to think about what this could mean for the entire neighborhood of Collinwood,” he says. “We didn't want to introduce market rate housing on the same site where we would then de facto displace people who needed affordable housing. We thought the best benefit in terms of kind of taking this parcel or this property into the future would be to open it up for public access, for the not only the neighborhood, but the region and the city to take advantage of.”

While Sargeant agrees that the infrastructure issues also make keeping housing options on the property infeasible and unaffordable, CNP wants to make sure residents have somewhere to go when the park closes.

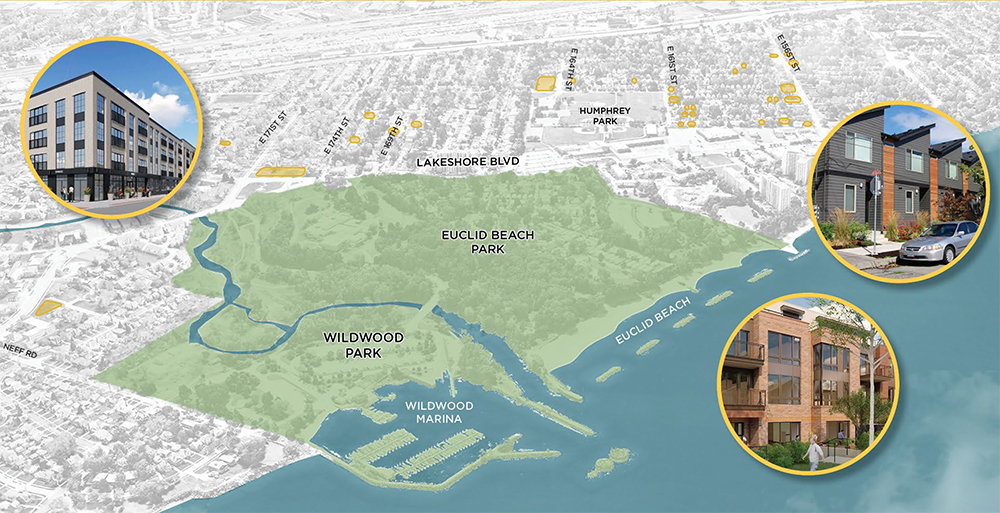

“We are working on a comprehensive housing strategy within the neighborhood,” he says, adding that CNP is working with Greater Collinwood CDC and leadership groups to create a plan.

“This is a mixed income strategy,” he says. “I think it will be a big part of potential relocation for a lot of these folks. We're looking at not just affordable housing, but housing in general across the board in the neighborhood.”

In terms of compensation or timeline for residents, Sargeant says, “I think that's really within Western Reserve’s ballcourt, not ours.”

Meanwhile, Sargeant says they have identified several acres of publicly-owned vacant land that could be converted into affordable and mixed income infill housing—thus, keeping residents in the neighborhood.

“Unfortunately, housing instability is a problem not only in the neighborhood, but across Cleveland,” he says. “I think generally our organization sees an opportunity here. We want these people to stay in Collinwood.”

Editor's note: This story has been edited to include clarifications.