Great Lakes Exposition: Great Depression distraction and Cleveland centennial celebration

In 1936, Cleveland was emerging from the lowest depths of the Great Depression. The year coincided with the centennial of Cleveland’s incorporation as a city. Impressed with the success of the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago a couple of years earlier, Cleveland leaders proposed a similar event here.

Great Lakes Exposition - Street of PresidentsPlans for the Great Lakes Exposition were subsequently put in motion.

Great Lakes Exposition - Street of PresidentsPlans for the Great Lakes Exposition were subsequently put in motion.

Led by Dudley Blossom, who put up $1.5 million of his own money, the fundraising, organizing, and planning proceeded quickly for the Great Lakes Exposition of 1936 and 1937.

An entirely new venue was constructed in a matter of 80 days, thanks to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s readily-available Works Progress Administration (WPA) labor, in time for the event to open on June 27, 1936. The facility covered 135 acres and was located where the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the Great Lakes Science Center, and the Cleveland Browns’ First Energy Stadium now stand.

The construction put money in the pockets of blue color workers and the overall event was expected to provide a generous boost to the area’s economy—the initial run of 100 days drew a total of four million visitors.

The expo ultimately ran in the summers of 136 and 1937—drawing seven million visitors who spent almost $70 million.

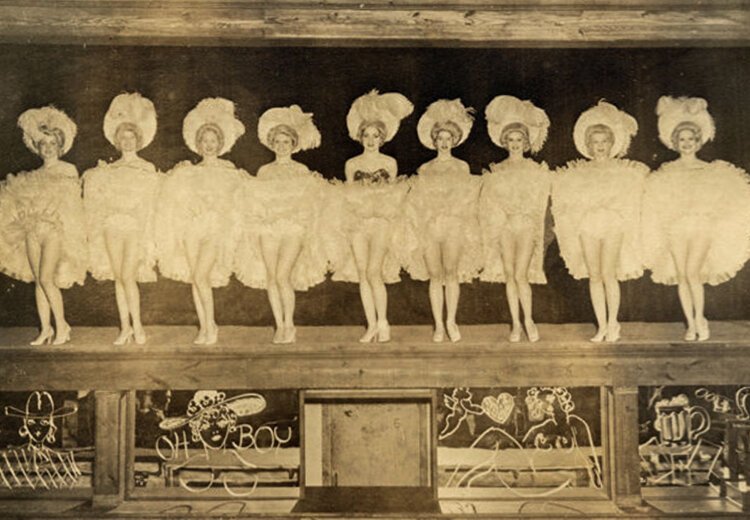

The exposition venue featured a large midway with dozens of attractions highlighting not just the Great Lakes region but the entire world.

Visitors could explore a wide range of attractions, which included rides, a theater, many dining venues, and a Hall of Progress that presented one of the earliest public demonstrations of television. For those with more elevated tastes, there was even an art gallery.

Billy Rose with Olympic swimmers Eleanor Holm and Johnny Weissmuller on a diving board at Billy Rose's Aquacade at the Great Lakes Exposition Over its two-year run, many prominent celebrities appeared at the exposition. These included noted swimmers Eleanor Holm and Johnny Weissmuller, who appeared in Billy Rose’s Aquacade. Weissmuller later achieved a measure of fame portraying Tarzan in a string of Hollywood films.

Billy Rose with Olympic swimmers Eleanor Holm and Johnny Weissmuller on a diving board at Billy Rose's Aquacade at the Great Lakes Exposition Over its two-year run, many prominent celebrities appeared at the exposition. These included noted swimmers Eleanor Holm and Johnny Weissmuller, who appeared in Billy Rose’s Aquacade. Weissmuller later achieved a measure of fame portraying Tarzan in a string of Hollywood films.

Olympic icon Jesse Owens is arguably the greatest athlete Cleveland has ever produced. The winner of four gold medals in the 1936 Berlin Olympics demonstrated his track and field skills at the Exposition to great acclaim.

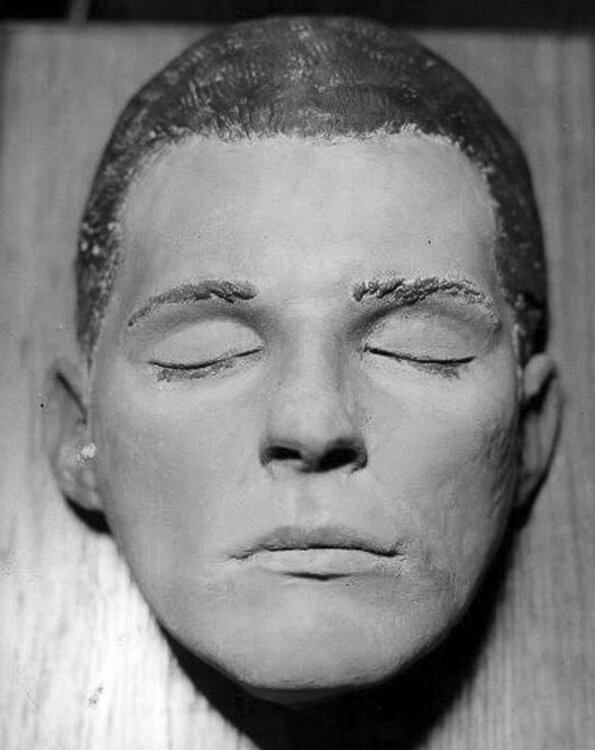

One of the more unusual sights at the event was an exhibit highlighting the Cleveland Police Department. It included death masks of unidentified victims of Cleveland’s notorious 1930s Torso Murders, aka the Kingsbury Run Murders.

It was hoped that someone in the large crowd of visitors would recognize these faces, but it was not to be, and almost nine decades later the crimes remain unsolved.

Visitors to the Cleveland Police Museum in the Justice Center may see these masks today. They are among the few remaining traces of the exposition.

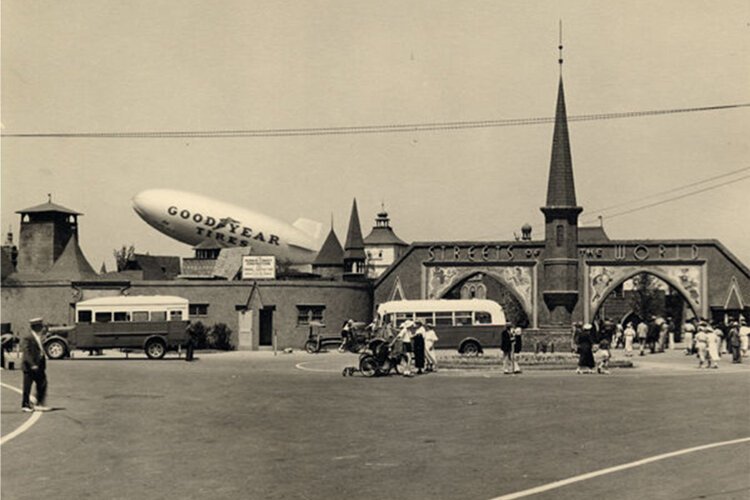

Streets of the World exhibit at the Great Lakes Exposition, with the Goodyear blimp in the backgroundNoted Cleveland landscape architect Donald Gray designed formal gardens located just north of Cleveland Municipal Stadium as an embellishment to the Exposition venue. The Donald Gray Gardens survived for 60 years, only to be destroyed in the construction of First Energy stadium.

Streets of the World exhibit at the Great Lakes Exposition, with the Goodyear blimp in the backgroundNoted Cleveland landscape architect Donald Gray designed formal gardens located just north of Cleveland Municipal Stadium as an embellishment to the Exposition venue. The Donald Gray Gardens survived for 60 years, only to be destroyed in the construction of First Energy stadium.

A silver half dollar coin was struck to honor the event, and the city's 100th anniversary of incorporation. The coins remain popular with collectors today.

The two-year run of the 1936-1937 Great Lakes Exposition was regarded as a success. As recently as 2010 the Great Lakes Exposition figured prominently in an exhibit, “Designing Tomorrow: America’s World’s Fairs in the 1930s,” at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C.

The Great Lakes Exposition lingers in the memories of the dwindling number of Clevelanders old enough to remember it.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.