Levi Scofield: Soldier, sculptor, architect

One of the finest architects Cleveland produced in the 19th Century was Levi T. Scofield. Known for some of Northeast Ohio’s most recognizable landmarks and many houses, it is his work that in many ways defined Cleveland’s look today.

Levi T. ScofieldScofield was born in Cleveland on November 9, 1842 to Mary and William Benedict Scofield. Both his father and grandfather were architects, and Levi trained under William after attending Cleveland Public Schools. Not much is known about his formal training, but Scofield was the first Cleveland architect to become a member of the American Institute of Architects.

Levi T. ScofieldScofield was born in Cleveland on November 9, 1842 to Mary and William Benedict Scofield. Both his father and grandfather were architects, and Levi trained under William after attending Cleveland Public Schools. Not much is known about his formal training, but Scofield was the first Cleveland architect to become a member of the American Institute of Architects.

But before becoming an architect and sculptor, like nearly all young men of his generation, at the age of 19 Levi Scofield was quickly caught up in the Civil War—responding to Abraham Lincoln’s call for volunteers by enlisting as a private in Battery D of the 1st Ohio Light Artillery.

This unit saw harsh service, fighting in the battles of Shiloh, Stone’s River, and Chickamauga. When his enlistment in this unit expired, he was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in the 103rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry. This unit saw action in the Atlanta Campaign and one of the war’s most desperate battles at Franklin, Tennessee in November 1864.

At war’s end Scofield mustered out on June 12, 1865 as a captain. He was 22 years old.

With the end of the war Scofield worked briefly in New York but soon returned to Cleveland to begin a architectural career of great importance.

Several notable examples of his work remain. Scofield was known for his massive, picturesque, Late Victorian style, with Gothic or Romanesque details. In addition to grand homes, he also designed many public buildings including a prison in North Carolina as well as multiple schools in Cleveland—notably his 1878 design of Central High School. He also designed several institutions to house and treat the mentally ill.

His Mansfield Reformatory became familiar to modern moviegoers as the scene of the 1994 film “The Shawshank Redemption” and it is notorious as one of the most haunted structures in the state of Ohio—bringing tourists, paranormal investigators, and even partiers to the abandoned prison.

Closer to home, one of Scofield’s best-known works is the Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Public Square, honoring Civil War veterans from Cuyahoga County and also often a subject of rumors and historic speculation.

General James BarnettProminent in local veterans’ affairs, Scofield was chosen to serve on a commission to plan this structure. He shared these duties with General James Barnett, his wartime commander from Scofield’s days as a field artilleryman. An artist as well as an architect, Scofield sculpted the figures displayed on the monument.

General James BarnettProminent in local veterans’ affairs, Scofield was chosen to serve on a commission to plan this structure. He shared these duties with General James Barnett, his wartime commander from Scofield’s days as a field artilleryman. An artist as well as an architect, Scofield sculpted the figures displayed on the monument.

Scofield’s wife, Elizabeth Clark Wright Scofield, was given the task of compiling the names of 9,000 veterans eligible to be honored by the Soldiers and Sailors Monument. This was a great responsibility, given the state of record keeping in that era as well as the desire not to overlook anyone. She was a notable citizen in her own right, having served as president of the YWCA, the first president of the Phillis Wheatley Association, and was mother of four children (including two sons who worked in their father’s architectural firm),

Surprisingly, many residents objected to placing the monument on Public Square. Streetcar companies feared it would disrupt traffic patterns. Property owners objected on the grounds that land values would be negatively impacted.

Wade Park and Lakeview Cemetery were also considered, but ultimately the objections were overcome, and the monument was constructed on the square’s southeast corner in 1894 where it has been a fixture for the past 127 years.

Scofield worked on this project for more than seven years without accepting payment. Additionally, he contributed $57,000 towards its completion.

Schofield Building 1910One notable structure is the Schofield Building (at some point Scofield, for no clear reason, dropped the “h’ from his last name), constructed in 1902 at the intersection of Euclid Avenue and Erie Street (present day East 9th Street). Today, the historic building has been renovated and restored as the Kimpton Schofield Hotel.

Schofield Building 1910One notable structure is the Schofield Building (at some point Scofield, for no clear reason, dropped the “h’ from his last name), constructed in 1902 at the intersection of Euclid Avenue and Erie Street (present day East 9th Street). Today, the historic building has been renovated and restored as the Kimpton Schofield Hotel.

This was a prominent downtown business address for years, as well as the location of Scofield’s own office on the 14th floor—which provided a clear view of the Soldiers and Sailors Monument. The building’s appearance was drastically altered in 1969 when a modern facade was added, which obscured the details Scofield incorporated in the original building. During the 2016 hotel conversion the modern facade was removed, and the exterior of the building is once again today as Scofield intended it.

Scofield designed many houses along Euclid Avenue’s Millionaire’s Row, including the long-gone 1878 R. K. Winslow house.

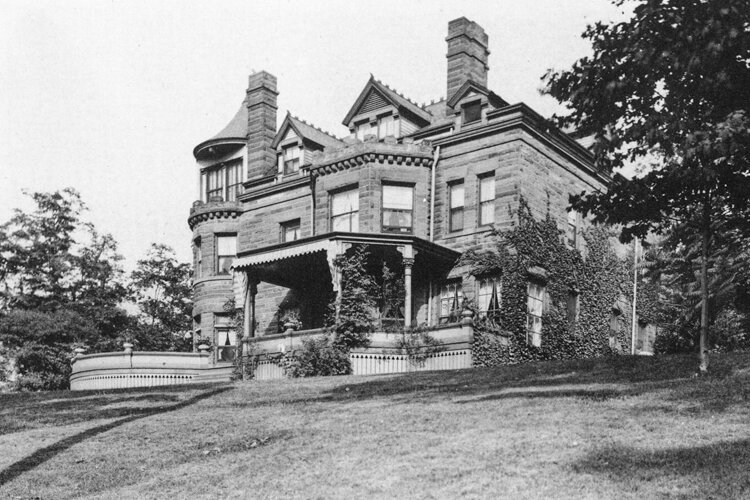

Another remarkable structure is Scofield’s home at 2438 Mapleside Road in Cleveland’s Buckeye-Woodhill neighborhood. The house is massive—three stories high and containing 6,000 square feet of living space. Completed in 1898 Scofield occupied the house until his death in February 1917.

Sold by his family in 1925 the house subsequently housed an order of nuns and then served as a nursing home before standing empty for many years and falling into disrepair. A movement to restore it is now underway.

An army officer in the Civil War Levi Scofield lived until the eve of the U.S. entry into WW I more than 50 years later. He was laid to rest alongside his wife in Lakeview Cemetery in an elaborate mausoleum he had designed years earlier. It was recently refurbished and occupies a prominent place in the cemetery.

His legacy is a group of remarkable buildings that have been part of the daily lives of Cleveland residents for more than a century.

About the Author: Tom Matowitz

Recently retired after a 37-year career teaching public speaking, Tom Matowitz has had a lifelong interest in local and regional history. Working as a freelance author for the past 20 years he has written a number of books and articles about Cleveland’s past. He has a particular interest in the area’s rich architectural history.