A century of hosting: 100 years of Republican National Conventions in Cleveland

One hundred years ago, Cleveland hosted the first of its three Republican National Conventions.

We’re still waiting for a Democratic one.

This imbalance might seem odd in today’s heavily Democratic Cleveland. But our city leaned Republican in 1924 and 1936, when it hosted that party. In 2016, Cleveland bid for both conventions and won the Republican one—disqualifying itself for the Democratic one.

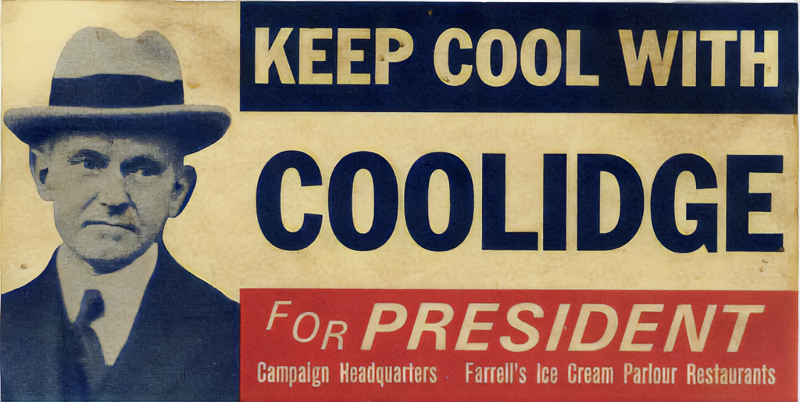

Each time, Cleveland was praised for its hospitality. Each time, the Republicans were hospitable to their top candidate, nominating him on the first round. Twice the nominee won the general election: Calvin Coolidge handily in 1924 and Donald Trump narrowly in 2016. But Republican candidate Alf Landon’s bid was crushed by Democratic incumbent Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1936.

The interior of Cleveland's Public Auditorium during the 1924 convention in June 1924The 1924 Republican National Convention from June 10 to 13, 1924 marked two firsts: It was the first one broadcast and the first with female voters as delegates.

The interior of Cleveland's Public Auditorium during the 1924 convention in June 1924The 1924 Republican National Convention from June 10 to 13, 1924 marked two firsts: It was the first one broadcast and the first with female voters as delegates.

Then as now, cities campaigned to get conventions. San Francisco and Chicago competed with Cleveland for the Republicans’ 1924 gathering. “Cleveland has a good chance but has to fight,” U.S. Senator Frank B. Willis told The Plain Dealer.

But Cleveland had several advantages, says John Grabowski, professor of history at Case Western Reserve University and the historian Western Reserve Historical Society.

“It was the right time to get a convention,” he says.

Cleveland was the nation’s fifth biggest city and Ohio’s biggest at the time. It was centrally located, at least for Republicans, given that the West was lightly populated, southern whites were heavily Democratic, and southern Blacks were widely barred from voting.

Local leaders offered the Grand Old Party a $125,000 expense account and free use of the acclaimed, two-year-old Public Auditorium, with about 11,000 seats. Cleveland also had enough lodgings for the crowd, and leaders pledged in writing to keep rates normal.

The clincher seemed to be the November 1923 death of President Warren G. Harding, the last of eight presidents to have lived in Ohio. Coolidge, Harding’s successor, endorsed Cleveland in tribute.

The Plain Dealer rejoiced, “For months, American attention will be centered on Cleveland. It is exactly the kind of opportunity for which the big auditorium was conceived, financed and built…The convention delegates and visitors will be welcomed not as partisans but as guests of a city which believes in political free thought and recognizes the obligations of a hostess.”

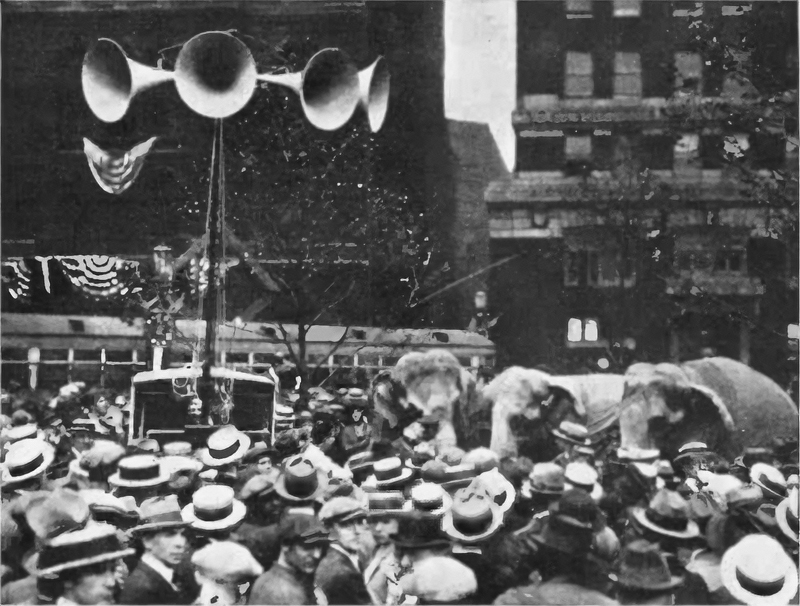

The rather reclusive Coolidge followed the custom of nominees to decline attending the event. That hardly spoiled the fun. There were fireworks, boat rides, banquets, and a parade of four elephants (the four-legged kind). A sound truck broadcast the convention on the streets, and young radio stations spread it much further.

1924 convention crowd outside Public Auditorium showing some of the 400 pillars on East 6th St facing southCrews raised 400 pillars along East 6th Street, each topped by a statue of an eagle. On June 9, the day before the convention, a windstorm toppled some.

1924 convention crowd outside Public Auditorium showing some of the 400 pillars on East 6th St facing southCrews raised 400 pillars along East 6th Street, each topped by a statue of an eagle. On June 9, the day before the convention, a windstorm toppled some.

The convention had 1,109 delegates, 118 of them women, who looked forward to casting their first presidential votes in November. As at past conventions, one delegate dressed as Buffalo Bill. The oldest delegate, D.C. Connell, 93, of Findlay, Ohio, got a seat on stage.

Handouts praised a Cleveland “humming with industrial activity; teeming with business enterprise and progressiveness; mindful always of maintaining its proud record of civic accomplishment; ever careful of the health, comfort and recreation of its people and every inhabitant a booster of his city.”

In the auditorium, John Philip Sousa conducted his band. Local Republican Congressman Theodore Burton gave the keynote address. Later speakers included Hallie Quinn Brown of Wilberforce, Ohio, president of the National Association of Colored Women.

From a rented house on Euclid Avenue, the Ku Klux Klan’s imperial grand wizard lobbied successfully to quash a proposed clause in the Republican platform denouncing his followers. The one-year-old Time Magazine, soon to move briefly to Cleveland, put his photo on the cover for a story about the “Kleveland Convention.”

On the third day, Coolidge was nominated, despite a few dissenters from Wisconsin. “With the exception of such a very few voters,” the chairman declared, “the nomination of Calvin Coolidge is made unanimous.”

Former Illinois Gov. Frank Lowden was chosen for vice president but declined. The role fell to General Charles G. Dawes, born in Marietta, Ohio.

The day after the convention, one of the elephants got loose and stampeded through downtown. The elephant trainer corralled it before any creature was harmed.

The next month, another party convened at Public Auditorium: The Progressives, who nominated Robert LaFollette and Burton Wheeler.

Gov. Landon on Public Hall Stage - Landon, governor of Kansas, was the Republican nominee for U.S. President in 1936 and defeated by Franklin D. Roosevelt.In November, the Republicans won 382 electoral votes and 54.0% of the popular vote. Democrats John Davis and Charles Bryan got 136 and 28.8%. The Progressives got 13 and 16.6%. And Cleveland got good returns.

“Cleveland is grateful for the innumerable compliments received,” The Plain Dealer printed. “There is no doubt that Cleveland can have more conventions if she wants them. And she ought to want them.”

The impressed Republicans returned in just a dozen years to Public Auditorium, newly rewired for better broadcasts. This time around, despite the Depression, Clevelanders raised $150,000 for the event.

The absent Landon was nominated handily on the first round, and Col. Frank Knox of Illinois became his running mate.

Afterwards, The Plain Dealer wrote, “We draw a long breath of mingled pride and satisfaction... Cleveland did a pretty good job, on the whole.”

Their foes, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Vice President John Garner, got 60.8% of the popular vote in November and all but eight of the nation’s 531 electoral votes.

Republican National Convention in Cleveland 2016In 2016, the Republicans gathered from July 18 through 21 at Quicken Loan Arena. Cleveland’s host committee raised $65 million for the convention. Complex barricades that were eight feet tall, helped delegates dodge protestors.

The convention was Cleveland’s first to be televised and streamed. Trump accepted the nomination in person, as had long been the custom.

Tourism Economics estimated that visitors spent $110 million. Despite objections from civil libertarians, Cleveland drew wide praise for being friendly and safe. The Plain Dealer reported, “The shine from Cleveland's performance as host city to the 2016 Republican National Convention has Republicans from Greater Cleveland and Ohio glowing with pride.”

Looking back, Emily Lauer, vice president of Destination Cleveland, says, “The convention infused revenue into our economy that wouldn’t have otherwise been realized, and, possibly more importantly, it launched Cleveland on a national and international trajectory in regard to awareness and reputation—as a leisure, business and meetings, and conventions destination.”

In the general election, Trump and running mate Mike Pence got just 46.2% of the popular vote to 48.2% for Hilary Clinton and Tim Kaine, but Trump won office with 304 electoral votes.

No efforts seem to be underway to bring either party here in the future. But Cleveland has hosted a few national gatherings of other political groups, including the National Convention of Black Freemen in 1948, the fourth National Women’s Rights Convention in 1853, and the so-called “Cleveland Convention” of 1864, when a Radical Democracy Party briefly arose.

For more about Cleveland’s national conventions, see CWRU’s Encyclopedia of Cleveland History and Cleveland Historical.