Urban décor: Cleveland’s many sculptures reflect city’s history, humor, unity, and divisions

In a construction zone beside RTA’s Ohio City station lies a big round sculpture by Loren Naji called “They Have Landed.” A plaque says the piece “alludes to the sphere... as well as planets, spaceships and alien life that just landed.”

Outside a gas station at Buckeye Road and East 89th Street stands a jagged, yellow, helmeted “Welder” by the late Rabbi Sidney Rackoff. According to a neighbor, Rackoff moved the sculpture there to memorialize a slain local. The victim wasn’t a welder, but the piece was the most suitable thing that Rackoff had.

Welder by Rabbi Sidney Rackoff stands at a gas station on Buckeye Road.Silly or solemn, classical or cutting-edge, free-standing or relief, beloved or controversial or all of the above, sculptures of many kinds enliven Cleveland’s landscape. They endure our rain, snow, droppings, pollution, and, sometimes, vandalism.

Welder by Rabbi Sidney Rackoff stands at a gas station on Buckeye Road.Silly or solemn, classical or cutting-edge, free-standing or relief, beloved or controversial or all of the above, sculptures of many kinds enliven Cleveland’s landscape. They endure our rain, snow, droppings, pollution, and, sometimes, vandalism.

They catch our eyes, stir our minds, and touch our hearts. They unite us and sometimes divide us.

An ongoing record

The Ohio Outdoor Sculpture Database lists 1,782 works, including a copious 504 works in Cleveland proper. Cleveland’s Sculpture Center started the list in the 1990s with funds from a national program called “Save Outdoor Sculpture!”

This spring, five Kent State University interns added more entries, photos, and descriptive details to the Ohio database. This summer, two more interns will do likewise.

The database’s curator, center trustee Bill Barrow, says that there’s no telling how many more outdoor sculptures remain to be found and catalogued in Cleveland and beyond.

For example, the database is missing Robert Indiana’s “Art,” which spells out that word and came in 2019 to a fitting site, the grounds of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Public reflection

Barrow is head of special collections at Cleveland State University’s library and an internet innovator. He created the university’s Cleveland Memory Project, which gives the public free access to 73,876 local images at last count.

James Simon’s 16-foot-tall “Buckeye Trumpet Man and Dog” jams silently but conspicuously at the Art and Soul of Buckeye Community Park on Buckeye Road.Barrow says that outdoor sculptures both serve the public and reflect it. “It represents what the community needs to say about itself and its famous people and events,” he says.

James Simon’s 16-foot-tall “Buckeye Trumpet Man and Dog” jams silently but conspicuously at the Art and Soul of Buckeye Community Park on Buckeye Road.Barrow says that outdoor sculptures both serve the public and reflect it. “It represents what the community needs to say about itself and its famous people and events,” he says.

For instance, James Simon’s 16-foot-tall “Buckeye Trumpet Man and Dog” jams silently but conspicuously at the Art and Soul of Buckeye Community Park, 17720 Buckeye Road, reminding locals about the neighborhood’s rich history of jazz.

James Muhammad, a volunteer who tends the park, says “That’s our icon here. This is Buckeye’s landmark.”

And nothing could be more of a Cleveland landmark than the figures known as “The Guardians of Traffic,” designed by Frank Walker. They stand on what’s now the Hope Memorial Bridge, named for William Henry Hope, one of the figures’ carvers and the father of entertainer Bob Hope.

Most public art can be enjoyed by anyone at any hour—with a few exceptions, such as monuments in cemeteries closed at night. “Art is for the people,” says Aubrey O’Brien, one of the Kent State interns. “Art should be accessible. Art should not be behind gates.”

“Judy’s Hand Pavilion” by Tony Tasset consists of a 21-foot-tall hand pressing its thumb into an Uptown plaza.The database includes statues, busts, archways, crosses, wartime cannons, and many other forms.

“Judy’s Hand Pavilion” by Tony Tasset consists of a 21-foot-tall hand pressing its thumb into an Uptown plaza.The database includes statues, busts, archways, crosses, wartime cannons, and many other forms.

“Gordon Square Paddle Ball” by Ben Haehn, Nathaniel Murray, and David Spasic consists of a big racquet tethered to a ball in mid-air.

“Judy’s Hand Pavilion” by Tony Tasset consists of a 21-foot-tall hand pressing its thumb into an Uptown plaza at Lake Avenue, Detroit Avenue and West 75th Street.

Nancy Dwyer’s “Meet Me Here” consists of benches spelling out those words outside Progressive Field.

Fame and controversy

Many of Cleveland’s outdoor sculptures are by acclaimed artists, such as Auguste Rodin, George Segal, Jim Dine, and native son Philip Johnson. Many are by obscure artists. Many are unsigned.

These works are widely seen and often controversial. In 1970, perhaps protesting institutional rule, a bomber destroyed the base and lower legs of Rodin’s “The Thinker” outside the art museum. The museum left the damage unrepaired, but the museum staff washes and waxes the sculpture twice a year.

In the 1980s, British Petroleum took over Sohio and rejected the commissioned Free Stamp by Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen. The stamp finally landed a few years later at Willard Park at East 9th Street and Lakeside Avenue, its base tilted toward BP’s 43rd-story boardroom.

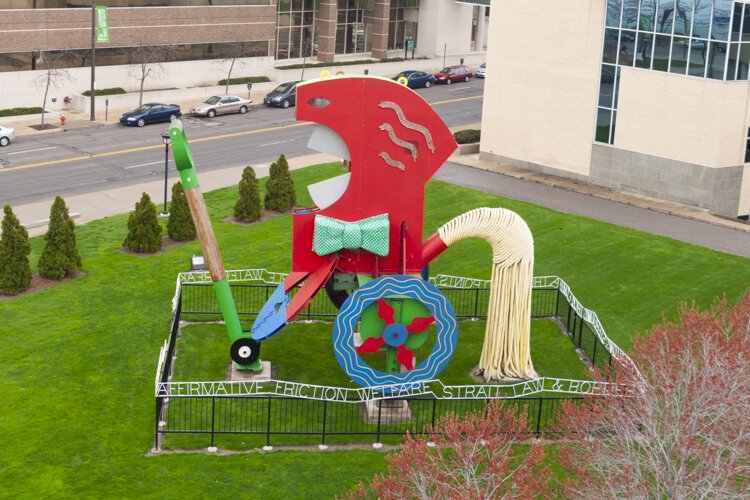

Billie Lawless’s “The Politician: A Toy” stands 42 feet tall, with a flapping mouth and snowy TV screens for eyes. It arose in 1996 in Midtown, then moved to Cleveland State University. Mayor Michael White criticized it, Lawless added trenchant messages, and Cleveland State covered up an off-color one.

Lawless sued, then agreed in 2019 to haul the sculpture to his studio in return for $50,000.

It’s keeping company there for now with Lawless’s “Didy Wah Didy,” which inspired more litigation. The neon piece shows a mushroom cloud with the words “Atomic Playground ahead,” and “Kids! Ride the big one!” Officials fought to banish it from a site near Interstate 70 in Columbus. For a while, Lawless put it Interstate 480 in Cleveland before taking it down.

But Cleveland probably hasn’t seen the last of these two works. Lawless says he plans to display them again sometime somewhere.

William Walcutt’s “Perry Monument”It’s odd how mobile big works can be. According to the database, “Welder” has moved eight times. William Walcutt’s “Perry Monument” moved several times around Cleveland and beyond. Now its figure of Commodore Perry is at Perry’s Victory and International Peace Memorial on Put-in-Bay, and its figures known as Midshipman and Sailor Boy are in the city hall of Perrysburg, Ohio.

William Walcutt’s “Perry Monument”It’s odd how mobile big works can be. According to the database, “Welder” has moved eight times. William Walcutt’s “Perry Monument” moved several times around Cleveland and beyond. Now its figure of Commodore Perry is at Perry’s Victory and International Peace Memorial on Put-in-Bay, and its figures known as Midshipman and Sailor Boy are in the city hall of Perrysburg, Ohio.

A replica of Walcutt’s whole monument stands at our Huntington Park.

In recent years, many activists have called for removing public monuments to leaders guilty of racism, sexism, or other wrongs. Right-wingers have denounced these demands as “cancel culture.” The Ohio database includes some debatable figures, such as Governor James Rhodes and General George Custer.

Barrow says he thinks the public should be free to change its mind. “Outdoor sculpture should be curated by the community, one way or another,” he says. “If people don’t feel like having General Lee in the midst of their public square anymore, they ought to be able to move it and make room for new people. The collection ought to be rotated sometimes and put in a separate place for historical study.”

For instance, the 28-foot-tall Chief Wahoo that used to grin from a wall at Municipal Stadium now grins at the Western Reserve Historical Society. “It wasn’t destroyed,” says Barrow, “but it’s no longer up for every camera covering an Indians game to focus on.”

The database suggests tour routes of sculptures in the Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati areas. `Barrow encourages the public to see the works, take pride in them, and support their preservation.

Some sculptures stand up well to our climate, but others weather. Says Barrow, “If you’re going to keep something on public display, you’re going to have to keep it up.”

Many entries in the database are outdated. “They Have Landed” and “Welder,” for instance, have been repainted with different colors since the database’s photos.

Many entries are incomplete. The entry for “Welder” says “Creator Unknown.” But, if you happen to know that the creator was Sidney Rackoff, and you search the database for his works, “Welder” pops up.

Barrow hopes members of the public will alert him to needed updates and additions and submit their findings.