creative workforce grants support artists while transforming 'rust belt' into 'artist belt'

Whether established or emerging, almost every artist struggles to find time for creative work, which necessarily trails behind responsibilities like work, family and paying the bills. Possessing an instinctive desire to fashion their experiences and ideas into art, artists scratch a few hours out of each day, savoring the time before they’re interrupted.

All the while, they never stop hoping for that lucky break -- the moment when their work is recognized and rewarded with an opportunity that helps them reach the next level.

Each year in Cuyahoga County, 20 talented artists get that lucky break. Thanks to the generosity of voters who approved a 2006 cigarette tax increase to fund arts and culture county-wide, a select group is picked to sit at the figurative head of the creative class. They’re bestowed with $20,000 Creative Workforce Fellowships to support their work.

The Creative Workforce Fellowship is a program of the Community Partnership for Arts and Culture that directly funds individual artists. The fellowship program is supported by Cuyahoga Arts & Culture (CAC), the organization that administers more than $15 million in public funding for the arts each year.

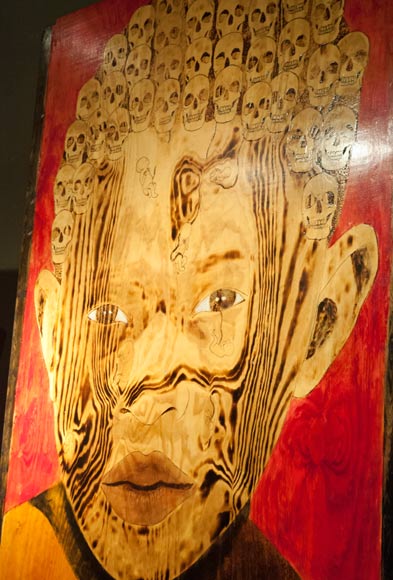

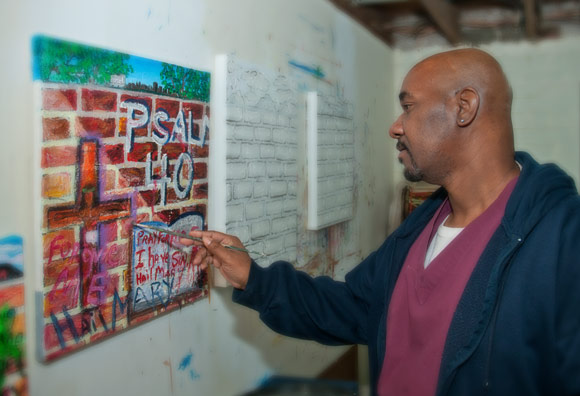

The 2013 crop of creative talent, announced in early December, includes Michelangelo Lovelace, an African-American painter who will use the funds to buy a live/work studio; Liz Maugans, a printmaker who is organizing a series of exhibitions about the impact of vacancy and the recession; and Gadi Zamir, a gallery owner whose shows will benefit nonprofit causes. The fellowships are helping to make their work possible, they say.

“When I found out, I cried,” says Maugans, cofounder of the printmaking co-op Zygote Press, whose personal work has long taken a back seat to being a mother of three and director of a nonprofit. “There’s very little funding that’s like this out there. This will allow me to do projects I’ve always wanted to do, but I was limited due to time and money.”

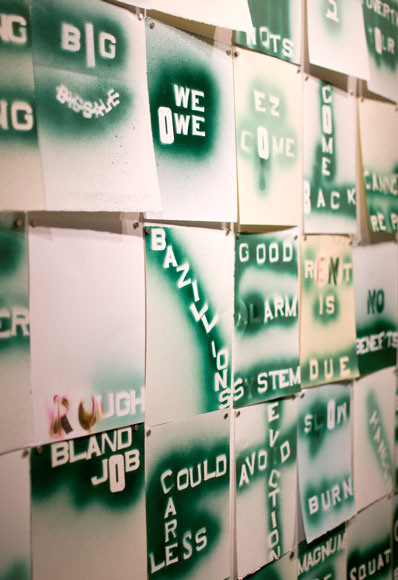

Maugans’ recent show at Arts Collinwood Gallery featured an interactive exhibit called “Half-Full Haiku,” which challenged audiences to write down ideas about how the Great Recession improved their lives. Maugans will organize responses into haiku which will be posted on a giant lettered sign that she bought from a now-defunct Dairy Queen.

Lovelace, a painter who works as a nurse’s assistant at MetroHealth and paints when he gets off work at 3 p.m., says the fellowship will allow him to realize the deferred dream of owning a home. “Without the fellowship, I wouldn’t have been able to do it,” he says. He also plans to host open studio events and talk to students about careers in art.

Although the fellowships are aimed primarily at helping individual artists develop their work, Susan DePasquale, Program Manager with the Community Partnership for Arts and Culture, says that the distinctive program offers a myriad of community benefits. Beyond supporting and retaining artists in Northeast Ohio, it also often inspires fellows to engage in community projects which make the arts more accessible to everyone.

“The community benefits reveal themselves in layers, and they can be surprising,” says DePasquale. “I think of Anne Trubek, a writer who won a fellowship last year. And one of the first things that she did after receiving it was to offer one of her ‘How to Pitch’ classes for free. That was pretty amazing. Normally, she wouldn’t have done that.”

The fellowships also raise awareness about the creative work of individual artists living in Cuyahoga County and brand the region to outsiders as an artist-friendly place to live.

“When panelists come in from out of town, one of the first things they say is, ‘I want to move here,’” says DePasquale, who believes that CWF is helping to raise awareness about Cleveland’s robust art scene. “They go back to their own communities and talk and blog about how amazing Cleveland is and the level of support we have for artists.”

One of the reasons CWF awards are the envy of artists throughout Northeast Ohio and beyond is that they come with precious few strings attached. Recipients can spend the money on just about anything they want, including artistic development and living expenses. Funds cannot be used to pay existing debt or for international travel, however.

Artists can apply for fellowships in the areas of literature, media, performing and visual arts. They are reviewed anonymously by a two-panel jury of artists, arts administrators and educators who live outside of Northeast Ohio. The quality of the artist work samples is the primary selection criteria, yet the panelists also weigh how applicants plan to use the funds during the fellowship year based on application responses describing the level of community engagement.

The focus on community engagement and public presentations represents a not-so-subtle change from previous years, when artists were not asked to furnish this information. The shift was recommended in part by CAC to demonstrate greater public impact; given that the 10-year arts tax will expire in three years and requires renewal, the move is timely. DePasquale says the new criteria was added to recognize what was already happening in the community with artists and community engagement.

“We kept hearing these beautiful stories of community empowerment that we hadn’t anticipated,” she says. “We talked about it as staff and thought, ‘What if we asked about this up front?’ We were interested in hearing these stories and helping artists plan and think about this in their own work. And for some artists, it was a little bit of a struggle.”

Yet other artists gravitated towards the idea of creating community benefit through their work almost instantly. Some even created new projects to bring their work to the public.

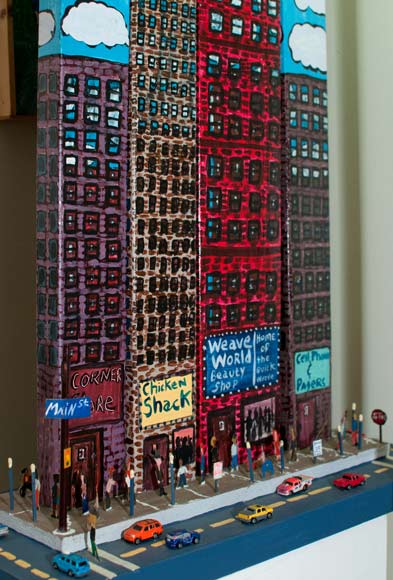

“A lot of times they say you have to go outside of where you are to be appreciated as an artist, but in this case, it happened in reverse,” says Gary Dumm, a graphic artist who is working with his wife Laura to design a Cleveland-themed mural for the side of the Orange Blossom Press building in Ohio City. Dumm invites Clevelanders to submit their ideas on the Cleveland Speaks Facebook page.

Dumm, who for 30 years worked as an illustrator for Harvey Pekar, credits the CWF for instigating the mural concept. “It’s buying us time to work on things we’re interested in.”

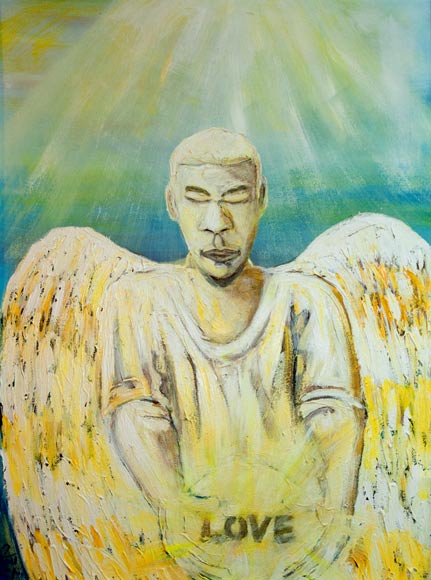

For other artists, like African-American painter Virgie Ezelle Patton, the CWF award is less a bolt from the blue than the well-deserved culmination of a lifetime of hard work. Patton, who has been painting for over 50 years, believes that she was previously excluded from achieving higher recognition because of her race and gender.

Patton, who has won many awards but whose work has not yet been collected by major museums, started her career as the only black student in her class at the Cleveland Institute of Art. She and her husband raised six children in the Glenville neighborhood, and she fought for years to find time for her painting.

“The ice is just starting to break, thank God,” says Patton when asked if today’s black artists find it easier to break into the mainstream art world than she did. “They didn’t want people to see a gifted black woman doing work that’s as good as anyone else’s. Many artists don’t get the respect they deserve until the end of their lives.”

“It feels so gratifying to receive the fellowship,” adds Patton, who is planning a show at William Busta Gallery that will include her painting of iridescent copper nymphs leaping out of Monet’s Water Lilies as well as her shimmering rendition of black Eve.

Maugans believes that the Creative Workforce Fellowship program is not only giving local artists their due, but also creating opportunities to involve new audiences in the arts. “It’s about engaging communities and making galleries welcoming places,” she says. “It’s about access. We want more people to be able to come and participate.”

Photos Bob Perkoski